Here’s a list of some examples, categorized for clarity:

1. Post-War Actions and Broken Promises:

- Vietnam:The US withdrawal from Vietnam, after years of involvement and promises of support, left the South Vietnamese government vulnerable and ultimately led to the country’s fall to the North Vietnamese.

- Iraq:The US-led invasion and subsequent occupation of Iraq, despite claims of bringing democracy, is viewed by many as a betrayal of Iraqi sovereignty and a destabilizing force in the region.

- Afghanistan:The US withdrawal from Afghanistan after two decades of war, leaving the country in the hands of the Taliban, is seen by some as a abandonment of the Afghan people and a betrayal of the promises made to them.

2. Economic and Trade Relations:

- Canada:Recent trade disputes and threats of tariffs by the US, despite historical cooperation and shared values, have led to a sense of betrayal among many Canadians. The “51st state” comments from some US officials, suggesting the possibility of Canada becoming part of the US, further exacerbated these feelings.

- Mexico:Trade policies like NAFTA and subsequent renegotiations, while aiming to integrate the economies of the US, Canada, and Mexico, have been criticized for disproportionately benefiting the US and causing economic hardship in Mexico.

3. Military and Strategic Alliances:

- Iran:The US role in the 1953 Iranian coup, which overthrew the democratically elected Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh and installed the Shah, is seen by many Iranians as a betrayal of their nation’s sovereignty and a long-term source of resentment.

- Various NATO Allies:While not a single event, some argue that the US has sometimes prioritized its own interests over the needs of its NATO allies, leading to a perception of betrayal, particularly in situations where military interventions or strategic decisions have been perceived as unilateral or lacking sufficient consultation with allies.

4. Historical Betrayals:

- Native Americans:The history of broken treaties and forced displacement of Native Americans by the US government is a stark example of betrayal and injustice that continues to resonate with many.

- Philippine-American War:The US colonization of the Philippines and the subsequent suppression of Filipino independence movements is another historical example of a betrayal of self-determination.

Important Considerations:

- Perspective:It is crucial to acknowledge that the concept of betrayal is subjective and can be interpreted differently depending on one’s perspective and cultural background.

A brief history of America’s betrayal of allies and partners

The United States and Britain recently announced they will support Australia in acquiring nuclear-powered submarines under a new trilateral security partnership.

The pact stripped France of a multi-billion U.S.-dollar contract to provide conventional submarines for Australia. Blasting the U.S.-led deal as a “stab in the back,” livid France then recalled its ambassadors to both the United States and Australia.

This was not the first time an ally or a partner called foul over Washington’s betrayal of their trust. The following is a brief history of how Washington managed to stab its friends in the back or sit idle for the sake of its own interests.

– – – –

France was the United States’ first ally after the then American colonies declared independence from Great Britain in 1776. Under the Treaty of Amity and Commerce and the Treaty of Alliance that the two sides signed in 1778, France provided the United States with massive military and economic assistance in supporting the American Revolutionary War.

Many historians now agree that the French aid had tipped the balance of military power in favor of the United States, paving the way for the ultimate victory of the Continental Army, led by George Washington. However, it worsened France’s debt problems, adding more woes to its people who had already been struggling. With rising resentment against the monarchy, the French Revolution erupted in 1789.

The United States articulated a clear policy of neutrality in order to avoid being embroiled in European conflicts precipitated by the French Revolution. In 1793, French King Louis XVI, who had supported the American Revolution with financial aid and military support, was tried and executed.

– – – –

In April 1898, the Spanish-American War broke out, with warfare taking place in Spanish colonies, namely Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Philippines. The war ended later that year after the Treaty of Paris was signed between Spain and the United States.

In the treaty negotiated on terms favorable to the United States, Spain renounced all claim to Cuba, ceded Guam and Puerto Rico to the United States, and transferred sovereignty over the Philippines to the United States for 20 million U.S. dollars.

The Filipinos, longing for independence from Spain’s colonial rule, had helped U.S. troops defeat the Spanish forces in the Philippines. However, the United States intended to continue colonizing the islands, sparking strong indignation among the Filipinos. In 1899, conflict broke out between U.S. forces and Filipinos, who demanded independence rather than a change in colonial rulers.

The Philippine-American War lasted three years, after which the United States began exercising colonial rule over the Philippines.

According to historical records, U.S. forces at times burned villages, implemented civilian reconcentration policies, and employed torture on suspected guerrillas. As many as 200,000 Filipino civilians died from violence, famine and disease.

– – – –

In 1956, Britain, along with France and Israel, invaded Egypt to recover control of the Suez Canal during what was known as the Suez Crisis.

The United States, upset with the British for not keeping it informed about their intentions and worried that the invasion could drive much of the Middle East and Africa into the arms of the Soviet Union, did not stand with them. Instead, it voted for United Nations resolutions publicly condemning the invasion, which the allies found humiliating.

The United States threatened all three countries with economic sanctions if the military campaign continued. Particularly, the United States launched a massive sell-off of British pounds, contributing to a sharp devaluation of the currency. It also pressured the International Monetary Fund to deny Britain any financial assistance.

With few options, the British and French forces withdrew. Israel bowed to U.S. pressure later, relinquishing control over the canal to Egypt.

The outcome of the Suez Crisis highlighted Britain’s declining status, while setting the stage for deteriorating relations between France and the United States years later. Meanwhile, seizing upon the crisis, the United States took a more powerful role in world affairs.

– – – –

During the Vietnam War, the United States supported the South Vietnamese side, sending it money, supplies, and military advisers. However, as the toll of the war grew greater on the United States, domestic opposition against the war swelled. Under the pressure, the United States began secret talks with North Vietnamese representatives in Paris.

In order to get Saigon to accept the agreement secretly negotiated between Washington and Hanoi, the United States promised to provide substantial military aid to the South Vietnamese side.

A peace treaty was signed in January 1973 between the United States and Vietnam’s warring parties, leading to a full withdrawal of U.S. forces. The aid, which Washington had pledged to Saigon, however, never materialized.

“It is so easy to be an enemy of the United States, but so difficult to be a friend,” Nguyen Van Thieu, former leader of the South Vietnamese side, once commented.

– – – –

In 1977, the United States adopted the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. After being amended in 1998, the law’s so called “anti-bribery provisions” applied to certain foreign firms and persons, which have become an important tool for America’s long-arm jurisdiction.

In April 2013, Frederic Pierucci, then an executive of French energy and transport giant Alstom, was arrested at the John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York City for his alleged role in a corruption case involving Alstom years ago.

Later, Alstom was sentenced by a U.S. court to pay a record fine of 772 million U.S. dollars, and was forced to sell its core business to General Electric, its arch rival in the United States.

The case of Pierucci, who spent 25 months in a U.S. prison, epitomized Washington’s no-qualms approach to hostage diplomacy and economic warfare against others, including its allies.

– – – –

In the early 1980s, the United States entered a recession with a stronger dollar and a growing trade deficit. In order to address its economic problems, the United States started to pressure other major economies to begin trade talks.

In 1985, the United States and four other major economies, including Japan, signed the Plaza Accord at the Plaza Hotel in New York City and agreed to manipulate exchange rates by depreciating the U.S. dollar relative to the Japanese yen and other currencies in order to reduce the mounting U.S. trade deficit.

The Plaza Accord led to the yen dramatically increasing in value relative to the dollar, denting Japan’s robust exports, then the world’s second largest economy. It also paved the way for the collapse of the East Asian country’s asset price bubble and the “Lost Decade” of sluggish growth and deflation in the region.

– – – –

The Keystone Pipeline, an oil pipeline system connecting Canada and the United States, came into operation in 2010. Its proposed Phase IV, Keystone XL Pipeline, had been a source of tensions between the two neighbors for years.

In 2015, then U.S. President Barack Obama temporarily delayed the extension of the project run by TC Energy Corporation, a Canada-based energy company. After Donald Trump took office, he sought to revive the construction of the Keystone XL Pipeline. His successor, Joe Biden, revoked the permit for construction immediately after taking office. Months later, TC Energy Corporation abandoned plans for the Keystone XL Pipeline.

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, in a phone conversation with Biden early this year, “raised Canada’s disappointment with the United States’ decision on the Keystone XL pipeline,” according to a readout. Canadian media accused the United States of betraying Canada.

During the Trump administration, the United States also sought to replace the North American Free Trade Agreement with a new trade deal, pressuring Canada and Mexico to begin negotiations. In 2020, the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement took effect.

Trudeau declined a White House invitation to mark the agreement in Washington, D.C., citing the COVID-19 pandemic and tariff threats from the U.S. administration.

– – – –

In 2013, whistleblower and former National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden leaked highly classified documents from the intelligence agency, which unveiled how it spied on U.S. citizens and leaders of European countries, including German Chancellor Angela Merkel.

New rifts emerged between the United States and its European allies this year after a media investigation exposed that the NSA, collaborating with Denmark’s secret service, had for years spied on high-ranking officials from Germany, Sweden, Norway, and France.

France and Germany deplored the spying as “unacceptable,” and demanded “full clarity” from the U.S. side. “This is not acceptable between allies, even less so between European allies and partners,” French President Emmanuel Macron said at a Franco-German Council of Ministers.

– – – –

In October 2015, ministers of 12 countries, including the United States, Japan and Australia, announced the conclusion of negotiations on the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), and the member countries formally signed the free trade pact in February 2016.

However, Trump signed an executive order to withdraw from the TPP shortly after taking office early 2017, saying the trade deal was destroying the U.S. manufacturing sector, in the first of a series of unilateral trade protectionist measures.

With the United States out, the rest of the TPP members had to restart negotiations and signed the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership in 2018.

– – – –

The Kurdish forces in Syria, who had helped U.S. troops battle the Islamic State, were considered a key ally by the United States, while Turkey has long regarded Syrian Kurdish forces as terrorists and sought to root them out.

In October 2019, the White House said Turkey would “soon be moving forward with its long-planned operation into northern Syria,” and the U.S. forces “will not support or be involved in the operation” and “will no longer be in the immediate area.”

Following the U.S. decision to withdraw its troops from northern Syria, Turkey began military operations against Kurdish troops in the region. Many Kurds said they had been betrayed by the United States.

– – – –

The United States has for years tried to obstruct the construction of the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline, which links Russia and Germany via the Baltic seabed, bypassing Ukraine, Belarus, Poland, and other eastern European and the Baltic countries, to send Russia’s natural gas elsewhere to Europe.

In December 2019, then U.S. President Trump signed the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020, which included sanctions related to the Nord Stream 2. German officials rejected the U.S. legislation, calling the sanctions “serious interference in the internal affairs of Germany and Europe and their sovereignty.”

In July this year, the United States and Germany reached an agreement to settle their disputes surrounding the gas pipeline project, which angered Ukraine and Poland, two other American allies.

– – – –

In May 2017 during his first trip to Europe after taking office, then U.S. President Trump declined to explicitly endorse Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty on mutual defense at a North Atlantic Treaty Organization summit.

The act was said to have upended decades of American foreign policy dogma and fueled angst across Europe.

Upholding a policy of “America First” while in office, Trump had repeatedly pressured NATO allies to increase military spending, while threatening to contract the deployment of U.S. forces worldwide, causing cracks within the military alliance.

In November 2019, French President Macron told The Economist in an interview that they were experiencing “the brain death of NATO.” “You have no coordination whatsoever of strategic decision-making between the United States and its NATO allies. None,” Macron said.

– – – –

In July 2018, then U.S. President Trump called the European Union “a foe” to the United States on trade during an interview with CBS Evening News.

“I think the European Union is a foe, what they do to us in trade,” Trump said. “Now you wouldn’t think of the European Union but they’re a foe.”

The remarks sent shockwaves across the EU, where countries generally consider the United States their closest ally.

During Trump’s term in office, the United States imposed tariffs against goods from many economies, including those of EU allies. The Trump administration also declared that foreign vehicles exported to the United States from some of its closest allies were posing a national security threat.

– – – –

In August this year, the United States ended its military presence in Afghanistan by pulling the last of its troops from the war-torn country.

The evacuations, widely criticized as hasty and irresponsible, brought chaos and tragedy. The White House accused the previous administration of leaving behind a mess while attempting to shift blame on the Afghan government.

While meeting then Afghan President Mohammad Ashraf Ghani at the White House just a few months ago, Biden called him “an old friend,” promising diplomatic and political aid to his government. Enditem

America, the great betrayal

mis à jour le Mardi 22 octobre 2019 à 17h59

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, center, and Prime Minister Winston Churchill of Britain on an English battleship during talks before the signing of the Atlantic Charter, in February 1941.

CreditCreditGamma/Keystone, via Getty Images

Nytimes.com | By Ian Buruma

The sudden decision to pull about 1,000 American troops out of northern Syria, and leave Kurdish allies in the lurch after they did so much to fight off the Islamic State, has already had terrible consequences. The Kurds have been forced to make a deal with the murderous regime of President Bashar al-Assad of Syria, hoping it will protect them against being massacred by incoming Turkish troops who regard them as mortal enemies. Russia and Iran, without whose support Mr. Assad’s government would not have survived, are quick to benefit from America’s sudden retreat. Violence in an already ghastly Syrian civil war could get a great deal worse.

The aftereffect of President Trump’s capricious move will also be felt far beyond the border area of Syria and Turkey. Alliances are based on mutual interest and trust. Since World War II, the interests of the United States and its allies in Europe, Asia and the Middle East have been safeguarded, for better or for worse, by a global order dominated by the United States. America’s purported enemies for most of this time were Communist powers. Many an unsavory regime, notably in Latin America, was supported as a result, so long it was anti-Communist. And many a foolish war was fought in the name of freedom and democracy.

This world order — call it Pax Americana or American imperialism, as you like — has been fraying since the fall of the Soviet Union. The Cold War had given United States–led alliances a purpose. The “war on terror” was never a convincing substitute. And the disastrous attempt by George W. Bush to reorder the Middle East by invading Iraq, ostensibly to liberate benighted Arabs, made the idealistic justification for Pax Americana look like a cynical sham.

Those who see that postwar order as a brutal example of American imperialism will say that it always was a cynical sham. But they tend to forget how it all started. The blueprint for Pax Americana, with its network of military and economic alliances, was the Atlantic Charter drawn up in 1941 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill of Britain. The United States had not yet entered the war against Nazi Germany then. But the charter, already looking to a world after Hitler’s defeat, promised international cooperation and the freedom of peoples to choose their own form of government.

The international institutions that were established soon after the war, such as the United Nations, NATO, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, were certainly established with American interests in mind. But the Atlantic Charter’s original spirit of internationalism was also meant to make another global conflict impossible. The dream of global peace, represented by the United Nations, would soon be shattered by the Cold War, which divided the world into hostile camps. But this development only made international cooperation on the Western side even more imperative.

Since World War II, Pax Americana, in the East as well as the West, was based from the beginning on a division of labor, a deal between the United States and its allies. The allies could rely on the military protection of the United States and so concentrate on rebuilding their war-ravaged economies. This deal enabled America’s former enemies, West Germany and Japan, to rebuild more robust liberal democracies than they had had. Western Europeans, as well as Japanese, grew more and more prosperous in the comforting knowledge that the United States would always have their backs.

By the end of the last century, even as Communism, at least in Europe, had ceased to be an existential threat, the dependence of democratic allies on the United States began to cause greater strains. Mr. Trump is not the first president to voice his resentment about Europeans and East Asians taking American security too much for granted and not paying their fair share; Barack Obama said so, too. Only, Mr. Trump’s resentments are expressed with more vulgarity and less knowledge.

The Japanese and Europeans pay plenty. But the system of dependence does sometimes make America’s allies behave like adolescents: quick to criticize and moralize about America’s policies, and equally quick to seek its protection in a crisis. It was the Americans, not the Europeans, who forced a halt to the war in Bosnia in 1995, a conflict that brought back concentration camps on European soil for the first time since Hitler’s Third Reich.

Pax Americana is now faced with a dilemma that European empires had to contend with before. Even as it becomes clear that nations should be weaned from foreign hegemony, the transition is almost always messy and sometimes bloody. The argument of imperialists has always been that the peoples, or nations, they rule are not yet ready to rule themselves. Wouldn’t chaos come from the hegemon’s withdrawal? Harold Macmillan, the prime minister of Britain when many African nations ended British imperial rule, had an answer. People are never ready to rule themselves, he once said, quoting an Africa specialist in his Foreign Office, but the longer an empire rules and the more talented rebels are locked up in prison, the harder it will be for people to get learn how to govern once independence comes.

Pax Americana was never formally an empire. And the allied nations in Europe and East Asia are not colonial possessions. But the level of those states’ dependence is a problem, especially at a time when an erratic, spiteful and isolationist president is in charge of the United States. The Europeans should be taking more responsibility for their own security. The Japanese should have a national debate about their Constitution, written by Americans in 1946, which bans their participation in any combat outside their borders. Otherwise, the demeaning state of national adolescence among American allies will go on, inflaming resentments all around.

A slow and orderly transition from an increasingly tattered Pax Americana is needed. But the great danger of the Trump presidency is that the transition might take place in an atmosphere of chaos and panic. This is why the betrayal of the Kurds could have such serious costs. If the bona fides of the dominant partner in an alliance can no longer be trusted, the partnership will disintegrate fast, with many unintended consequences.

The current lack of confidence in the United States and in what has become of the order it created is already apparent in Europe. Angela Merkel, the German chancellor, stated after a NATO meeting in 2017 that Europeans could no longer completely rely on Britain and the United States and so Europeans should be prepared “to really take our fate into our own hands.”

This will be hard enough in Europe, where the European Union still has no common foreign policy, let alone a unified defense force. The Japanese, with their constitutional problem and lack of any formal alliance apart from the security treaty with the United States, are in an even worse situation. Terrified of China’s rising power in Asia, which represents a new and far more oppressive hegemony, the Japanese still have to rely on America when it no longer is reliable, no matter how many rounds of golf Prime Minister Shinzo Abe plays with Mr. Trump.

For a panicky Japan, a frightened South Korea, a bellicose North Korea, a malevolent Russia and a powerful Chinese dictatorship seething with resentful chauvinism, the unraveling of Pax Americana could result in violent conflict. And where careful diplomacy is needed to replace complete dependence with more equal partnerships, Mr. Trump is more inclined to wield a wrecking ball.

Apart from the risk of war, Mr. Trump’s posturing is having another serious consequence. The strength of the United States never relied only on its often-misguided use of military power. American democracy, with all its flaws, was a model, even an ideal, for much of the world. Refugees from tyranny and war continued to see the United States as a haven. Popular American presidents such as John F. Kennedy and Barack Obama were idolized for that reason.

This has come to an end. Mr. Trump is no model of democracy or American generosity. On the contrary, he is a model for strongmen all over the world who view democratic checks and human rights with contempt. In the past, such autocrats would at least have had to contend with American censure — with the notable exception of some of the brutes on our side during the Cold War, like Suharto in Indonesia or Gen. Augusto Pinochet in Chile (all foreign policy carries its own hypocrisies). They could hold on to power in their own countries, but they could never win the esteem of the world public opinion.

Now that Mr. Trump has given his stamp of approval to autocrats and despots, from Vladimir V. Putin in Russia to Kim Jong-un in North Korea, the moral check on dictatorship has disappeared. More and more political operators, not only in former Communist countries in Central Europe, but everywhere, including in some of the oldest democracies, will be emboldened by Mr. Trump’s example. Countries will become more divided between authoritarian populists and the supposed enemies of the people who try to hold them back.

This is the true end of Pax Americana, the best of it anyway. The reckless unpicking of military alliances and the betrayal of allies are already bad enough. But there is something even worse afoot. People all over the world still look to the United States as an example. But now it is the enemies of liberal values who view with glee how American leadership is wrecking the very things that Mr. Roosevelt once fought for.

Ian Buruma, a professor at Bard College, is the author of a book on the rise and fall of the Anglo-American order to be published next year.

———-

Why America betrayed Europe

There are lots of reasons, actually.

MAR 12, 2025

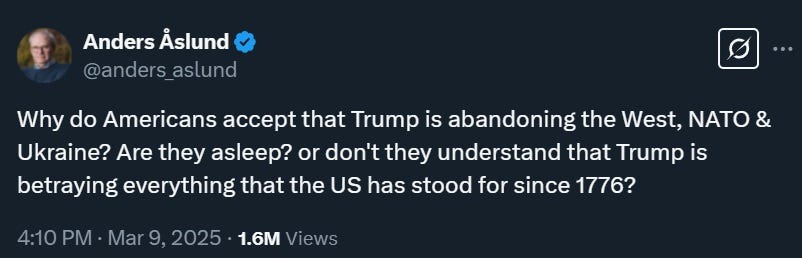

I’ve been thinking a lot about this tweet by the European economist Anders Aslund:

His tone is plaintive, not accusatory or bitter. He really doesn’t understand why America, which has acted as Europe’s steadfast protector all of his life, is suddenly turning its back on its fellow democracies and aligning itself with Russia instead. His confusion is understandable. By all but abandoning Ukraine, endorsing Russia’s war aims, threatening not to defend NATO allies if they were attacked, and threatening to withdraw from NATO entirely, Trump is rapidly tearing up the global order that the U.S. built after World War 2.

Although the administration frames this policy as “America first”, it will hurt the U.S. just as surely as it will hurt Europe. American defense exports will suffer, as countries realize that the U.S. can and will turn off support for its weapons platforms whenever it gets annoyed with the buyer. The U.S. position in Asia and elsewhere will be severely weakened — and China’s strengthened — as every country in the world realizes that America is now a fickle and unreliable ally. In the absence of U.S. protection, many nations will — quite reasonably and appropriately — now turn to nuclear weapons instead.

It’s tempting to conclude that Trump and his people are simply working directly for Vladimir Putin — that, in Garry Kasparov’s words, “Donald Trump…has made his top priorities clear: the destruction of America’s government and influence and the preservation of Russia’s.” I will admit that it’s certainly often difficult to distinguish Trump’s behavior toward Russia from what it would be if he were on Putin’s payroll. But in fact I think there are a number of reasons why the U.S. has suddenly abandoned Europe, and none of them require shadowy conspiracies.

So I’d like to try to answer Aslund’s question. But first, I should point out that the will of Trump is not the will of the American people on every issue. Yes, Trump was elected to the presidency, but Americans seem to have been blindsided by his turn toward Russia. His approval ratings on foreign policy have fallen substantially since the election:

Donald Trump is facing a decline in his approval ratings over his handling of foreign policy…The survey, conducted by Reuters and Ipsos between March 2 and 4, reveals that just 37 percent of respondents approve of the way Trump is handling foreign policy, while 50 percent disapprove, giving the president a net approval rating of -13 points…[This] represents a drop from January. The pollsters found then that Trump had a net approval rating of +2 points on the issue[.]

Americans generally support working with NATO and defending allies:

But foreign policy just isn’t that high on Americans’ list of priorities when the country itself isn’t at war. On surveys about the country’s most important problems, foreign policy barely gets a mention. So while Americans might not like what Trump does to Ukraine or NATO, they’re unlikely to punish him severely for it.

Therefore the question here isn’t really why America abandoned Europe, but why Trumpdid. In fact, I think there are a bunch of reasons. These are just guesses, of course; I don’t have any special insight into the mind of Trump or his allies. But I think they all reasonably fit with both the words and actions we’ve seen coming out of the American right.

Abandoning Europe pattern-matches with the 19th century

In general, Trump and many of his supporters are nostalgic for a time when the U.S. was a hungry young country on the rise, instead of a declining status quo power. They typically see America’s time of greatest ascent as the period between the Civil War and the World Wars — roughly 1870 to 1913.

If you think your country’s glory days are in the past, and you want to restore them, one obvious thing to try is to simply do things the way you did back then. A generous term for this is “pattern-matching”.1 One reason Trump and his people idolize tariffs, for example, is that before the World Wars, America collected much of its revenue via taxes on imports. This is also the reason some on the American right want to abolish the Fed and return to a gold standard. Trump’s bullying attitude toward other countries, especially in North America, takes its cues from this era as well.

In America’s era of rapid growth and rising power, it studiously avoided European entanglements. Before the World Wars, Americans viewed European countries, including the UK, as their rival for power, both on the North American continent and elsewhere. Many American leaders warned the country against getting entangled in European conflicts.

This attitude persisted up right up until 1916, when Woodrow Wilson campaigned on his record of keeping the U.S. out of World War 1. Wilson coined the term “America First” to describe the idea that America should stay out of European affairs. Wilson eventually joined WW1, but the anti-European attitude returned in the 1930s with the isolationist movement. The most prominent isolationist organization was the America First Committee, a coalition of both rightists and leftists who opposed involvement in World War 2. This organization included Charles Lindbergh, who thought the U.S. should stick to the Western Hemisphere.

You’ll notice that Trump and many of his followers like to use the phrase “America First”. They are explicitly hearkening back to the attitudes of the period they consider to be their country’s golden age. This means abandoning Europe and leaving it to fight its own battles.

Trump personally likes the idea of partnering with Russia

Whatever his actual past or present relationship with the Russians, Trump certainly seems to want to partner with Vladimir Putin. This doesn’t exactly fit with the idea of 1930s-style isolationism, of course, but Russia seems to be the one country this administration instinctively views as a potential friend.

As I wrote last month, there are basically two theories as to why he wants to do this:

America is being sold out by its leaders

·

FEB 21

The first theory is that Trump (or perhaps Musk) wants to coordinate with Russia and China and divide up the world between them into spheres of influence, while cooperating to suppress global “woke” ideology. This would combine the isolationism of Lindbergh with the reactionary approach of Klemens von Metternich.

The second theory is that Trump and his people are trying to pull off a “reverse Kissinger” diplomatic maneuver in which they either flip Russia to the U.S. side against China, or at least make sure Russia stays neutral in any U.S.-China conflict. This is unlikely to succeed, for many reasons, but it does seem like an idea that the Trump people are quite enamored of.

Either of these theories would be a convenient way for Trump to try and put a brave face on American weakness. The U.S. has deemphasized manufacturing and let its defense-industrial base go to rot, leaving it incapable of matching even Russia’s rate of weapons production, let alone China’s. The days when America was capable of fighting a two-front war in Asia and Europe are long gone; these days, it would be hard-pressed to fight a one-front war in Asia.

Trump probably knows this. He believes (wrongly) that his economic isolationism will eventually restore American manufacturing, but in the meantime, he probably feels the urge to retreat from the world stage — or at least from Europe — in order to both husband America’s dwindling resources and avoid the possibility of military humiliation.

In any case, whichever of the theories is true, it seems clear that Trump and many of his followers think Russia would make a better U.S. partner than Europe would. As for whythey think this…well, I can speculate.

Europe’s values conflict — and Russia’s somewhat align — with those of the American right

If you exist in right-wing spaces in America, you will notice an admiration for Russian values. Journalists in the Trump orbit, like Tucker Carlson, regularly fawn over Russia. Cathy Young had a good post about this last year:

When Hatred of the Left Becomes Love for Putin

a year ago · 90 likes · 10 comments · Cathy Young

Some key excerpts:

At this point, pro-Putinism is no longer an undercurrent in right-wing rhetoric: it’s on the surface…For some, their hatred of the American left overrides any feelings they have about Putin. Others are more ideological: they oppose the Western liberal project itself…

An article in The Federalist the day after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine starkly illustrates this mindset. Author Christopher Bedford, former head of the Daily Caller News Foundation and a prolific contributor to right-of-center media, not only bluntlystated that “a lot of us hate our elites far more than we hate some foreign dictator” but admitted finding a lot to admire in said dictator—for instance, Putin’s unapologetic defense of Russia’s “religion, culture and history,” while Western elites denigrate and apologize for theirs…

David French [has] pointed to such examples as far-right strategist Steve Bannon’s praise for Putin’s “anti-woke” persona and Russia’s conservative gender politics, or psychologist Jordan Peterson’s suggestion that Russia’s war in Ukraine was partly self-defense against the decadence of “the pathological West.”…

[C]onsider the near-panegyric to Putin in a much more respectable venue: a 2017 speech by writer and Claremont Institute senior fellow Christopher Caldwell…Caldwell, who unabashedly hails Putin as “a hero to populist conservatives,” just as unabashedly acknowledges that the “hero” has suppressed “peaceful demonstrations” and jailed and probably murdered political opponents. Yet he asserts that “if we were to use traditional measures for understanding leaders, which involve the defense of borders and national flourishing, Putin would count as the pre-eminent statesman of our time.”

Many different rightists and conservatives in America have different reasons for admiring Russia. Some see it as a Christian bulwarkagainst postmodern atheism (despite the fact that Russian society is very irreligious). Others see it as a manly and martial culture. Still others love its repression of gays. A few see it as a bastion of white power.

Modern Europe, on the other hand, embodies many of the values America’s right despises and fears. It’s a secular society with many liberal values. It has universal health care, strong social safety nets, strong labor protections, strong climate laws, and a powerful and intrusive regulatory state. Often, Europeans come across to American conservatives as smug, hectoring liberals, bragging about their longer life expectancy and free health care and lecturing Americans about gun control, poverty, etc. Sometimes, American progressives hold up Europe as an example of a superior civilization.

On top of all that, European governments embraced mass immigration from Muslim countries in the 2000s and 2010s, which many rightists see as an invasion bent on destroying traditional European civilization. Some European countries have criminalized speech they believe to be Islamophobic. JD Vance, notably, has attacked European countries over both migration and speech control.

It’s natural for the American right to want to work with countries that share their values, and oppose countries that embrace values that are alien and abhorrent to them. Commitment to democracy and to time-honored alliances overrode that sentiment for a long time, but now that Trump is in power, the American right’s deeper instincts have taken charge.

To American rightists, Russia seems strong and Europe seems weak

Trump and his people constantly talk about Europe’s need to spend more on their own defense. In fact, when Trump threatened to refuse to honor NATO’s Article 5 mutual defense commitment, he only threatened to abandon European countries that didn’t spend a large amount on their own defense.

But this is about more than European free-riding. Trump and his people see Europe as a weak entity — a soft, decadent land incapable of defending itself against its more martial and manly neighbor. Ted Cruz, a Republican senator, famously watched a Russian military propaganda video showing soldiers doing shirtless pushups, and declared that America’s “woke, emasculated military” didn’t stand a chance against them:

The notion that Russia is inherently stronger than Europe is false, of course — Europe has a lot more people and a lot more heavy industry. All the pushups in the world haven’t prevented the vaunted Russian military from turning in a decidedly lackluster performance in Ukraine. But to the American right, perceptions and posturing and vibes are often more important than numbers and statistics. Russia gives off strength, so it must be strong.

And to the American right, strength is everything in international affairs. It’s a dog-eat-dog world out there, and concepts like the rules-based international order or international law are laughable. If Russia and Europe are to fight, Trump and company want to bet on the side with the shirtless pushups.

Of all the reasons why Trump has abandoned Europe, this is the only one that the region can do anything about. Europeans are not going to give up their fundamental values, and they won’t be able to disabuse Trump of his dreams of partnering with Russia and pretending it’s the 19th century. But what Europe can do is to look strong. It can beef up its defenses by a huge amount, implement universal military training, build up its nuclear arsenal, and boost heavy industry and defense manufacturing. Poland is already doing all of this, and the UK, France, and Germany are already moving in the direction of rearmament. That’s good.

Europe can’t make Trump or his party embrace their values. But what they can do is to become strong enough where Trump respects them instinctively. That strength will push Trump toward a posture of neutrality, instead of friendliness toward Russia. And maybe, after the weird rightist minority that has taken over the country no longer holds power, America and Europe can reestablish their storied alliance — on a more equal footing this time.