A Catham House Analysis

Political transitions in Ethiopia and Sudan offered the promise of more democratic, civilian-led government and increased regional stability in the Horn of Africa. But contestation between old and new political forces has disrupted both transitions since 2020. Meanwhile, relations between the two countries have been characterized by growing discord over cross-border issues, including the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, the disputed territory of Al Fashaga and the war in northern Ethiopia. These bilateral tensions and domestic crises threaten to undermine security and development across the region.

This paper assesses the domestic contexts in Ethiopia and Sudan and the contentious cross-border issues that are damaging relations. It also details the range of regional and international interventions to date. The paper concludes with recommendations on how international stakeholders can coordinate responses to support political transition, and achieve stability for both countries and the region.

contents

Summary

02 Background: Placing current domestic crises in context

03 Untangling Ethiopia and Sudan’s shared cross-border issues

04 Regional and international attempts to reduce cross-border tensions

05 Policy implications for international stakeholders

Summary

- Cross-border tensions and interlinked crises in Ethiopia and Sudan jeopardize security and development in those countries and across the Horn of Africa. International efforts to support regional stability should work towards coordinated responses, addressing the intersection of crises and causes of instability within and between both countries.

- Political agreements – aimed at ending hostilities in northern Ethiopia and seeking to secure a more robust civilian government in Sudan – provide an opportunity to renew both transitions if the necessary diplomatic backing is forthcoming.

- Transitions in both countries from 2018 offered the promise of more democratic, civilian government and increased regional stability. But contestation between old and new political forces has seen those transitions veer off course since 2020, amid a brutal war in Tigray and other parts of northern Ethiopia and a catastrophic military coup in Sudan.

- Since 2018, relations between Ethiopia and Sudan have been characterized by growing discord over a range of cross-border issues, including the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, Al Fashaga and the war in northern Ethiopia. While tensions have deepened, open conflict seems unlikely following a detente between the leaders of both countries. Yet the situation is fragile and efforts to restore relations must be reinforced. If cross-border issues are left to fester, tensions could again escalate, with grave implications for regional stability and affecting humanitarian, development and economic outcomes.

- Until the signing of the Pretoria Agreement by Ethiopian parties in November 2022, the African Union and the Intergovernmental Authority on Development struggled to intervene effectively in either context. The range of domestic, regional and international interventions reflect a divergence among stakeholders as to what stability entails for both countries and the Horn – and how it can be achieved.

- Other regional and geopolitical stakeholders – including Egypt, Eritrea and the Gulf Arab states – are pursuing their own, often competing, interests in Ethiopia and Sudan, complicating prospects for de-escalation and resolution. The United Arab Emirates (UAE) has largely pursued securitized and transactional approaches. Strategies prioritizing cooperative stability, with reference to popular civilian demands, would boost both transitions and ease cross-border tensions, improving outcomes for the UAE’s economic and food security interests.

- A reinvigorated US role and greater cooperation with partners – including the EU, the UK, Saudi Arabia and the UAE – could encourage partners to move beyond securitized approaches; instead crafting policies that show greater sensitivity to national and subnational contexts in the Horn.

- More cohesive international engagement is needed to support stability within Ethiopia and Sudan, building confidence and platforms to calm relations and resolve damaging cross-border disputes. Enhanced alignment between regional envoys is necessary and, if effectively connected with continental and regional diplomatic mechanisms, could provide the foundations for longer-term stability and integration.

01 Introduction

Volatile transitions in Ethiopia and Sudan contribute to, and are negatively affected by, bilateral and cross-border tensions. Coordinated policy responses are needed from international stakeholders to restore trust and achieve regional stability.

Ethiopia and Sudan, both in the middle of contested political transitions, are contending with cross-border tensions over an array of issues that have increasingly pitted the two regional powers against one another. While recent high-level diplomatic engagement between the two countries has partially eased the situation, continued bilateral tensions not only affect the trajectory of the political transitions of each country but pose a threat to broader regional stability and security.

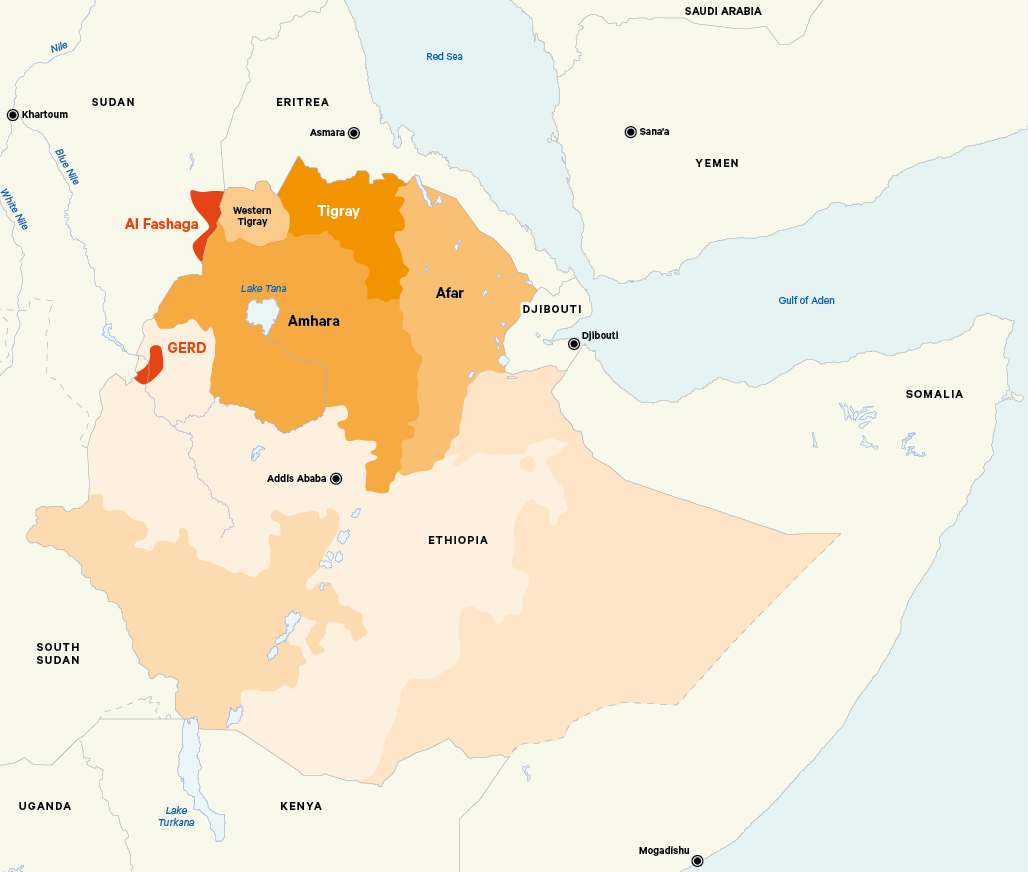

Chief among these sensitive cross-border issues is the ongoing disagreement between Ethiopia, Sudan and Egypt over the operation of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), situated on the Blue Nile river near Ethiopia’s border with Sudan. With the dam almost complete, reaching an agreement on its operation – particularly regarding water releases during periods of low or high river flow – is considered an existential problem for the three countries.

Years of discord over the GERD underpins the unresolved historical dispute over the shared border between Ethiopia and Sudan. This dispute is connected to both persistent tension over the contested fertile farmland of Al Fashaga and apparent Sudanese support for Tigrayan opponents of the Ethiopian federal government over the last two years. Federal troops and allies from Eritrea and Ethiopia’s Amhara region had been fighting Tigrayan forces until a tenuous ceasefire was agreed on 2 November 2022. With Ethiopia distracted by the early phases of conflict in Tigray, Sudanese forces moved to push Ethiopian farmers and paramilitaries out of Al Fashaga in December 2020. This military action angered the Ethiopian government and elite stakeholders from the Amhara region, as well as broader popular constituencies within Ethiopia, and prompted ongoing sporadic clashes between Ethiopian forces and the Sudanese military.

With limited room for manoeuvre and compromise, Ethiopian prime minister Abiy Ahmed Ali and the leader of Sudan’s October 2021 coup, General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, have been compelled to guard their own domestic political positions by demonstrating their readiness to defend their respective states’ interests over the GERD, Al Fashaga and Tigray. This political posturing has heightened the risk of direct confrontation between the two states. Added to this, a broader set of regional and geopolitical stakeholders – including Egypt, Eritrea and the Gulf Arab countries – are actively pursuing their own, often competing interests, complicating the context and prospects for de-escalation and resolution. Despite this, these external forces are integral to easing tensions in Ethiopia and Sudan.

Diplomatic stakeholders have dedicated considerable attention and effort to supporting the fragile transitions in Ethiopia and Sudan, and to recovering those processes as each has veered off course. However, the possible wider impact of tensions between the two countries has not been fully appreciated. If allowed to fester, these negative dynamics should rather be regarded as a dangerous hindrance to any attempts to revive those transitions. Continental and regional responses from the African Union (AU) and the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) proved largely ineffectual until the signing in November 2022 of the Cessation of Hostilities Agreement (or Pretoria Agreement), aimed at ending hostilities in northern Ethiopia, with the two organizations presenting a disunited front up to that point. Meanwhile, the US and the EU have failed to invest sufficient diplomatic capital in addressing bilateral and cross-border pressures between Ethiopia and Sudan, although scope remains for more robust and influential engagement. The Gulf Arab states – in particular, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) – have largely pursued a transactional and securitized approach to Ethiopia and Sudan. However, a strategy focused on prioritizing cooperative stability would improve outcomes for the Gulf states’ economic and food security interests in the medium and long terms.

The progression of both the Pretoria Agreement and the Framework Agreement, seeking to secure a more robust civilian political transition in Sudan, provides an opportunity to reset the political transitions in both countries, if the necessary sustained diplomatic backing is forthcoming. However, achieving improved regional stability will require international partners to think beyond domestic concerns and work across the set of shared issues that affects both countries, as well as the relations between them. Individual international stakeholders should use regional diplomatic mechanisms to link and better coordinate their bilateral engagements in Ethiopia and Sudan. Improved coordination will have the benefit of solidifying bilateral relations and regional outcomes. The implementation of joint cross-border measures would restore trust and facilitate further collaboration and conflict avoidance. External stakeholders should play a robust role as investors and guarantors of such measures. Absent this evolved approach to Ethiopia, Sudan and the wider Horn of Africa region, tensions are not only likely to increase again in future, but also to become more dangerous and destabilizing.

Figure 1. The Horn of Africa

Just a few years ago, Ethiopia and Sudan looked set for encouraging new chapters in their fraught histories. In Ethiopia, newly selected prime minister Abiy Ahmed began repairing relations with Eritrea in July 2018 and set a course for uniting his ethnically diverse country, following years of growing opposition to the ruling party. In Sudan, months of civilian protests culminated in the military’s ouster of president Omar al-Bashir in April 2019 after 30 years of dictatorship, laying the foundation for democratic rule. Today, both countries are undergoing fraught and bloody transitions which have vast national and regional implications, and in which numerous powerful external actors have a keen and sometimes damaging interest.

Clashes between old and new political forces in both countries have violently disrupted political reform and fuelled economic crises. In Ethiopia, conflict in the northern region of Tigray began in late 2020, pitting the region’s forces against the Ethiopian federal army – with the latter supported by Eritrea and a mix of other Ethiopian regional forces, most notably from the neighbouring Amhara region. It also propelled fighting across northern, central and western regions of Ethiopia. The war has stirred up ethno-nationalist and secessionist sentiments, directly contributing to hundreds of thousands of deaths (and leading to credible accusations of atrocities on both sides), threatening the unity and integrity of the country’s federal system, and exacerbating tensions with neighbours to the point that the conflict has threatened to engulf the entire region. Sudan’s civilian-led transition was derailed by a military coup in October 2021, leading to near-daily street protests and dashing hopes of a permanent shift towards democracy. All of this has been accompanied by attempts on the part of regional and geopolitical stakeholders to influence the political process in often contradictory ways.

Along with these domestic concerns, interconnected issues have pitted the Ethiopian and Sudanese governments against each other, drawing in communities living on either side of the shared 740-km border. Sporadic military clashes over the fertile agricultural land of the Al Fashaga region, and repeated accusations of proxy support for each other’s rebel groups, demonstrate the mistrust and limited working relations between the new leaders in Ethiopia and Sudan over the last two years. These issues should be viewed as part of a larger existential regional power rivalry over the management of the GERD. Increased pressure from domestic crises in both countries has led to both governments hardening their opposing stances, worsening tensions between them over these cross-border disputes.

Along with domestic concerns, interconnected issues have pitted the Ethiopian and Sudanese governments against each other, drawing in communities living on either side of the shared border.

If these cross-border issues are left to fester, tensions could escalate considerably. While open conflict between Ethiopia and Sudan seems unlikely at present – particularly in the wake of the Tigray ceasefire and attempts by Abiy and Burhan to restore relations – the situation is fragile and efforts to restore good relations need to be reinforced. Renewed and sustained hostility between the two countries would have grave implications for regional stability, affecting humanitarian, development and economic outcomes. It could also draw other regional actors into a wider struggle.

International stakeholders working to defuse these tensions need to factor the potentially combustible interaction of domestic and cross-border issues into their policy responses. Substantial multilateral and bilateral diplomatic efforts in Ethiopia and Sudan to date have largely failed to account for the intertwining of such issues. In fact, international stakeholders have often worked at cross purposes – influenced by their own, sometimes incompatible, interests. If they are to address the growing regional impact of cross-border disputes, partners concerned with long-term stability in the Horn of Africa should work to understand the fundamental linkages between the domestic crises in Ethiopia and Sudan, and should formulate policy responses accordingly. They should also better align approaches that seek to boost levels of engagement and trust between the Ethiopian and Sudanese governments.

Methodology

This research paper is based on field research conducted by the authors in Ethiopia and Sudan between 2022 and 2023. That research consists of semi-structured key informant interviews, as well as some online interviews. Desk-based research examined a variety of secondary sources. These included, among others: academic and policy research on both countries and their wider regional dynamics; official documentation, including the Pretoria Agreement and Framework Agreement documents; and news sources from Ethiopian, Sudanese and international outlets.

The sampling for the key informant interviews sought to represent a broad range of actors and interests engaged in domestic and diplomatic interventions in both countries – including governments, political parties, regional and international actors, academics, analysts and civil society representatives. The sample included senior leaders from across the Ethiopian and Sudanese political spectrum, representatives of the AU and IGAD, as well as diplomats from key regional states, Western governments and multilateral organizations.

It is important also to acknowledge the difficulties in conducting this research. Research was not conducted in other parts of the broader region, such as Eritrea or the UAE. However, a short field visit was made to Egypt. A limiting consideration was the safety of the researchers and potential research participants. While the focus on foreign policy considerations reduced the potential risk of conducting interviews, the political and security situation in parts of Ethiopia and Sudan meant that not all actors could be consulted and not all societal positions could be included. Additional secondary sources were consulted to fill gaps where possible.

02 Background: Placing current domestic crises in context

Contestation between old and new political forces in Ethiopia and Sudan has seen those countries’ transitions veer violently off course in the last two years.

Recent developments in Ethiopia and Sudan contrast starkly with the situation at the end of 2019. At that time, there was broad-based optimism about the future in both countries and an abundance of international goodwill and support for governmental reforms. Besides this, there was a general sense of hope that reforms in Ethiopia and Sudan could enhance regional stability and provide a template for political transitions elsewhere in the Horn of Africa.

However, relations between the two countries, which had been cordial for over a decade, were unsettled by seismic changes within both governments from 2018, resulting in increasingly strained working relations at the governmental level, with a lack of communication contributing to heightened disharmony over several cross-border issues.

From hope to hostility in Ethiopia

Abiy’s ascent to the office of prime minister in April 2018 followed several years of popular protests that eventually ended the 27-year rule of the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), an ethnic federalist coalition dominated by the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF). As the country’s first Oromo leader, Abiy’s rapid rise to power dramatically redrew the political and ethnic dividing lines in Ethiopia, shifting the country’s centre of power southwards from the northern highlands. In his first year of office, Abiy pushed forward with liberalizing policies, including releasing political prisoners, enabling the return of exiled opposition figures, increasing press freedoms, installing a more inclusive and gender-balanced cabinet, and initiating institutional reforms. He also made international overtures: in July 2018, just three months after his election, he moved to end Ethiopia’s long-standing border dispute with Eritrea.1 These early reconciliation efforts and reform agenda bought Abiy much support and goodwill, particularly among Ethiopia’s urban elites. It enabled him to claim a mandate to address Ethiopia’s deep ethnic divisions, while the creation of the Prosperity Party (PP) in late 2019 sought lay the foundations for centralized political reform in the country.

However, Abiy’s efforts to rebalance Ethiopian politics faced challenges from rival parties and the country’s embedded structures of ethnically based federalism.2 Rising insecurity across the country in part reflected the huge number of competing interests and demands for recognition, as well as resistance from the EPRDF old guard and from ethno-nationalist opposition groups opposed to Abiy’s centralizing ambitions.

Escalating tensions with the TPLF culminated in November 2020 with the outbreak of conflict in Tigray, with the PP-led federal government confronting the TPLF-led Tigray regional administration. The war quickly provoked broader ethnic tensions, with the country’s ethno-nationalist movements roughly splitting into two camps: (i) the federal government, which primarily drew on ethnic Amhara paramilitary and youth groups (known as ‘Fano’), corralling troops from the Afar region and other regions where possible; and (ii) the TPLF, which during the conflict allied itself with other pro-federalist forces such as the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA) and Gumuz militias in Oromia and Benishangul-Gumuz states, respectively, as well as minority Kimant and Agaw militias from the Amhara region. Eritrean forces intervened in support of the federal government, contributing to a brutal two-year civil war that has so far cost up to 500,000 lives, according to some reports.3 Violence has also spread to other parts of the country – notably Oromia, where in February 2023 the regional president called for reconciliation talks with the OLA, which have subsequently been taken forward by the federal government.4 Moreover, contestation between Ethiopia’s two most populous regions, Oromia and Amhara, has seen hundreds killed and thousands displaced in 2022 and 2023.5

A fragile humanitarian truce in Tigray, declared in March 2022, failed to engender the confidence-building required for sustained talks between the warring parties. Instead, both sides used the time to prepare for renewed conflict. Fighting duly restarted in late August with an offensive by federal government and Eritrean forces, alongside Amhara and other Ethiopian groups, against Tigray. The land and air assault upended fragile arrangements for humanitarian access in that state, reimposing a federal government blockade on the region, disabling critical public services and exacerbating an already grave humanitarian crisis.6

The AU-brokered Pretoria Agreement was eventually signed by the federal government and the TPLF on 2 November 2022, in Pretoria, South Africa. Ultimately, the autumn offensive had significantly weakened the Tigrayan forces, who, unable to break through heavy Amhara, federal and Eritrean fortifications in western Tigray to reach the Sudanese border, had limited options for resupply. The Tigrayan leadership concluded that a ceasefire and political settlement were preferable to another sustained period of guerrilla warfare, which would have further devastated the civilian population.7 Subsequent talks between the parties have led to progress on several fronts, including the facilitation of improved humanitarian access, the resumption of flights into Tigray and the slow restoration of critical services in Tigray such as banking, electricity and telecommunications. Tigrayan disarmament and demobilization prefaced the return of federal forces to major cities in the region, and their assumption of responsibility for the protection of federal infrastructure, including airports and military installations.

The normalization of relations between the regional and federal governments has led to the establishment of an interim regional administration in Tigray, with the TPLF selecting Getachew Reda as its president-elect, and the Ethiopian parliament voting to rescind the party’s designation as a terrorist organization in March 2023. It is also expected that regional elections will be rerun.8 However, critics within Tigray are sceptical both about the Pretoria Agreement, which they see as a win for the federal government, and about whether an elite bargain between the government and TPLF can produce a broad-based interim arrangement. Many of those critics feel that an administration inclusive of opposition parties, civil society and diaspora groups is needed to reconfigure longer-term governance structures in Tigray, as well as to ensure that accountability and transitional justice are not ignored.

It is hoped that the ceasefire and goodwill created through dialogue and continued incremental gains will help to secure a sustainable peace in Tigray and northern Ethiopia. However, potential internal and external spoilers remain. Elites in the Amhara region are concerned about what peace between the federal government and TPLF will mean for the future administration of territories contested by Amhara and Tigray, with Amhara forces having captured vast areas of western Tigray in November 2020. Any initiatives to alter the status quo – including the suggestion of interim arrangements in those territories – will be fiercely resisted.

In addition, the conflict in northern Ethiopia has becoming increasingly regionalized and has recalibrated cross-border power dynamics and alliances, with far-reaching consequences for politics and peace in the Horn of Africa. Eritrea’s role in the conflict remains a crucial impediment to peace. The administration in Asmara could seek to influence outcomes in its favour by leveraging its expanded connections to political and military actors in the Amhara region. Moreover, Sudan’s interests along its shared border with Ethiopia, including those concerning Al Fashaga and the GERD, remain a significant factor in its approach to Tigray. The Sudanese government has concerns over the mobilization of Amhara nationalists in response to its takeover of territory in Al Fashaga. It could choose to maintain its influence over and support for elements of the TPLF/Tigray Defence Forces (TDF),9 both as a way of retaining leverage over the Ethiopian federal government and as a response to the actions of Amhara regional actors and Eritrea.

A stalled transition in Sudan

Meanwhile, in Sudan, fragile progress towards greater stability and accountable, inclusive governance was halted by a military coup in October 2021 that derailed the country’s transition to civilian rule. The coup ended a power-sharing deal between civilian and military authorities that had been in place since August 2019. The deal had been undermined by ongoing internal divisions within and between both the civilian and the military camps.

Despite the military’s insistence that its takeover would bring stability, the country has in fact become less stable as a result. Regular street protests in the capital, Khartoum, and beyond have placed even greater pressure on the already foundering Sudanese economy. Popular unrest shows no sign of abating, amid attempts to bring back into government members of the deeply unpopular Islamist old guard from the Bashir era. The military has responded with violent crackdowns that have killed over 120 people and injured thousands more, primarily in Khartoum. This political chaos has evidently affected the neglected peripheries of Sudan’s east and south, and particularly its western region of Darfur, where lawlessness and violence have soared, with hundreds having been killed and tens of thousands displaced since early 2022.10

More dangerously for stability in Sudan, divisions within the military itself have been growing. The country’s two most powerful leaders – the head of the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) and chairman of the country’s Sovereign Council, Burhan, and the commander of the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and vice chairman of the Sovereign Council, General Mohamed Hamdan Dagolo (known as Hemedti) – have been increasingly opposed and are working to cultivate domestic and international support to weaken one another.

Political chaos has evidently affected the neglected peripheries in Sudan – particularly its western region of Darfur, where lawlessness and violence have soared, with hundreds having been killed and tens of thousands displaced since early 2022.

Hemedti has captured key sectors of the economy and increased the strength of the RSF, which rose in prominence during the final years of Bashir’s rule. The RSF has, with some limited success, styled itself as the guardian of Sudan’s marginalized peripheral regions,11 and represents an inherent challenge to the SAF, which is largely led by officers from communities in Sudan’s Nile Valley heartland. Figures from those heartland communities have dominated the country’s post-independence politics and economy. Though the two wings of Sudan’s military jointly executed the October 2021 coup, they are locked in battle for domestic supremacy.12

Amid the current political vacuum, Sudan’s economy and public services have deteriorated, insecurity has risen and foreign policy is muddled by the competing power centres within the military. It is hoped that the signing of a political framework agreement in December 2022 between the Forces for Freedom and Change-Central Council (FFC-CC) – a coalition of civilian political groups, professional associations and civil society groups – and the military will lead to the establishment of a reform-minded and credible civilian government. However, the military has shown little will to abandon either politics or its role in the economy. Instead, it is attempting to shape and capture the political process including the result of the election – expected to be held after two years of renewed transition, as per the Framework Agreement – by cultivating allies across the political spectrum and sidelining pro-democracy groups, which have struggled to unify.13 Credible elections look increasingly unlikely, with the foundations for greater transparency and inclusion laid by the earlier civilian-led transitional government crumbling before they could be properly established.

Diplomatic and economic pressure by the AU, IGAD, the UN, the EU, the UK and the US for the restoration of civilian rule has thus far failed to persuade the military.14 In the meantime, Burhan and Hemedti have worked to strengthen bilateral engagement with Gulf Arab countries, Egypt, Israel and Russia, seeking political and financial support to help resist the demands of both protesters and diplomatic stakeholders keen to see a civilian dispensation in Sudan. Regional and geopolitical stakeholders suspicious of a democratic government are themselves divided about which side of the country’s military they want to see prevail. During the transition to date, Egypt and Saudi Arabia have been overtly supportive of Burhan and the SAF, while Israel, Russia and the UAE have backed Hemedti’s RSF.15 Sudanese analysts, Western diplomats and UN officials suggest that more recent Emirati and Saudi Arabian engagement in Sudan has ostensibly supported progress towards a working political process, albeit with a view to legitimizing a military-led or military-friendly government through elections.16

03 Untangling Ethiopia and Sudan’s shared cross-border issues

Growing discord over a range of cross-border issues – including the GERD, Al Fashaga and the war in northern Ethiopia – has deepened mistrust between Ethiopia and Sudan over the last two years, impacting both countries’ political transitions and threatening regional stability and security.

Relations between Ethiopia and Sudan have been negatively affected by the epochal changes in both governments, in 2018 and 2019 respectively. These separate domestic developments have not resulted in the sort of close personal relationships between leaders that had characterized Ethiopian–Sudanese relations during the long respective tenures of Meles Zenawi and Bashir. The new relationship began well, with Abiy being praised for his role in brokering the agreement between Sudanese military and civilian leaders that established Sudan’s civilian-led transitional government in August 2019. But relations deteriorated following the start of the war in Tigray in 2020, first due to Abiy’s firm rejection of Sudanese offers to mediate, and second due to the SAF’s forceful takeover of Al Fashaga at a time when the Ethiopian army was distracted by the new conflict in Tigray.17

Figure 2. Eritrea, Ethiopia and Sudan tri-border area

The contestation over Al Fashaga and apparent Sudanese backing for Ethiopian opposition forces from Tigray and Benishangul-Gumuz is intertwined with the larger regional matter of the GERD dispute – an existential issue for both states, as well as Egypt.18 Tigrayan and Gumuz forces, along with Oromo militia, have fought against the Ethiopian military and regional security forces, particularly the Amhara Special Forces (ASF) and Fano regional militia – with Gumuz forces reported to have attacked deliveries of construction materials for the GERD, demonstrably slowing the dam’s completion.19

Beyond strategic calculations around the GERD, Sudanese government interests in the Tigray conflict are, in large part, the result of historical links between the Sudanese military and the TPLF. But they are in part linked to the dispute over Al Fashaga. Since sweeping into Al Fashaga in the weeks after the start of the conflict in Tigray, Sudanese regular forces now occupy this border area almost entirely, giving Sudan control over 600,000 acres of valuable agricultural land.20 Al Fashaga’s location along 250 sq km of the border also makes it crucial to Tigrayan interests keen to secure an access route into Sudan for trade and humanitarian supplies, as well as any military assistance necessary in the event of a resurgence of conflict. With Eritrea to the north, and Afar and Amhara federal states to the east and south, Sudan remains Tigray’s only prospective friendly boundary – although the crucial strip of land along the border was occupied early in the conflict by Ethiopian federal, Amhara and Eritrean forces, who recognized the strategic importance of the area as a potential supply route.

The GERD

Disagreement over management and operation of the GERD lies at the heart of tensions between Ethiopia and Sudan. Built on the Blue Nile in Ethiopia’s Benishangul-Gumuz region, just 30 km from the border with Sudan, the GERD is nearing completion, with the Ethiopian government announcing in March 2023 that 90 per cent of the dam was finalized.21 The dam, Africa’s largest, began generating electricity in February 2022, after 11 years of construction work.21 The Nile River states directly affected by choices made by Ethiopia in relation to water flows – Egypt and Sudan – have engaged in years of sporadic talks with Ethiopia over the dam’s operation. To date, the three countries have failed to finalize an agreement, although most technical issues reportedly have been resolved.22

Those talks have foundered over an array of issues: Egyptian insistence on applying prior treaties on the use and distribution of Nile water that disadvantage Ethiopia;23 Ethiopian insistence on a non-binding agreement over water-sharing and operation of the dam; disagreement over the structure and legality of a dispute resolution mechanism;24 and differing views over drought mitigation and how much water to release from behind the dam during periods of high and low water flow.25 Coordination on water releases from the GERD’s 74 billion-cubic metre reservoir is imperative to regulate downstream flows and avoid disruption of Sudan’s Roseires dam, which lies 100 km downriver from the GERD and holds just one-tenth of its volume.26 In 2020, a water release from the GERD without prior notice disrupted the Roseires water pumps,27 and in 2021 the filling of the GERD dam basin caused the Roseires dam to clog with excess silt, halting its turbines.28 In a sign of progress, the parties agreed in mid-2022 to share data on GERD operations to support operational and irrigation planning by downstream states.29

Sudan’s civilian-led transitional government sought to tread a narrow path of even-handedness in regional relations, which included efforts to mediate on outstanding technical and legal issues around the GERD.

After initially favouring the GERD megaproject, Sudan has grown more sceptical of the project over time. Former President Bashir initially backed the dam’s construction, correctly anticipating benefits including improved control of damaging Nile flooding, improved irrigation for farming and the purchase of excess electricity to supplement Sudan’s weak and unreliable power grid. But Bashir’s ouster prompted a change in Sudan’s stance. Sudan’s civilian-led transitional government sought to tread a narrow path of even-handedness in regional relations, which included efforts to mediate between Egypt and Ethiopia on outstanding technical and legal issues around the GERD.30 Following the October 2021 coup, however, the Sudanese military’s long-standing relationship with Egypt’s armed forces came to the fore, with the two armies conducting large-scale military exercises that heightened Ethiopian unease.31 Policy towards the GERD likewise hardened under military leadership. The conflict in Tigray, which fuelled violence along the Ethiopia–Sudan border and heightened bilateral tensions, also raised questions among Sudanese officials regarding Ethiopian intentions and prospects for ensuring smooth dam operations amid ongoing instability. However, the recent detente between the leaders of Ethiopia and Sudan offers some hope for a return to closer alignment on the GERD between both countries.

Egypt, meanwhile, has always opposed the dam. It views unfettered access to Nile waters as an existential issue: 98 per cent of the country’s nearly 100 million people live close to the Nile, which provides around 90 per cent of Egypt’s water needs.32 Egypt’s reliance on the river fuels its concerns about the potential for Ethiopia to assert unilateral control over its flow – a concern shared by Sudan.33 Egypt likewise fears that Sudan could divert a larger share of the Nile over time to support expanded agriculture, motivating efforts to maintain close relations.34 To reinforce its stance against the GERD, Egypt has sought to influence both US and EU positions on the issue.35 It has also sought alliances among other Nile Basin countries such as South Sudan and Uganda. Before the Ethiopia–Eritrea rapprochement of 2018, Egypt had cultivated relations with Eritrea, partly to rile the Ethiopian government.36

Al Fashaga

The resurgence of a century-old dispute over ownership and use of the border region of Al Fashaga – lying in Sudan’s Gedaref state and flanking both Tigray and Amhara in Ethiopia – is an especially sensitive flashpoint, given the direct involvement of both militaries. Since 1996, the highly prized and fertile region has been predominantly cultivated by thousands of Ethiopian Amhara and Tigrayan farmers, with the tacit acquiescence of Sudan’s government. Following the ouster of al-Bashir, however, Sudanese interest in regaining Al Fashaga intensified.37 Shortly after the start of the conflict in Tigray, the SAF pushed into Al Fashaga, capitalizing on the shifting focus of Ethiopian federal and Amhara forces. Sudan quickly reclaimed nearly the entire area of Al Fashaga with little fighting, evicting thousands of Ethiopian farmers.

Sudanese officials now insist that a return to prior farming and soft border arrangements in Al Fashaga will only be possible if Ethiopia accepts Sudanese sovereignty over the territory.38 Sudan’s claim dates back to the Anglo-Ethiopian Treaty of 1902 and a subsequent effort to demarcate the border between Sudan and Ethiopia in 1903. The unofficial border line drawn as part of this effort – the Gwynn Line (named after the British officer who had led the attempt to demarcate) – places Al Fashaga inside Sudan, although the 1972 exchange of notes between the two countries provides for negotiated demarcation.

Sudan has worked to consolidate its hold over Al Fashaga by expanding Sudanese farming in the area, while also building military fortifications, bridges and roads.39 Sudanese communities with land claims in the region hailed the SAF’s takeover, boosting the army’s standing in parts of eastern Sudan that traditionally have not viewed the military favourably. Such heightened political favour has great value for the SAF as it works to build popular support for its role in the country’s transition.40

The Al Fashaga issue has subnational implications, as important Ethiopian and Sudanese constituencies – including business figures linked to Emirati interests in agricultural production – demand that Prime Minister Abiy and General Burhan respectively secure the fertile territory for farming.41

After Sudan’s reclamation of Al Fashaga, Abiy has been under pressure to defend what many Ethiopians, particularly the Amhara, view as historically and rightfully Ethiopian territory. Amhara elites have pressed the Ethiopian federal government to respond both diplomatically and militarily to Sudan. However, apart from an early burst of violence, the Ethiopian and Sudanese militaries have mainly avoided direct confrontation. Instead, sporadic cross-border clashes have taken place involving Amhara militias, which Sudan alleges are backed by the Ethiopian and Eritrean militaries. Those clashes have allegedly killed dozens of Sudanese soldiers.42 Violence has also erupted due to disputes between Ethiopian and Sudanese farmers over the control of agricultural lands in Al Fashaga and other parts of Gedaref state. In mid-2022, the Sudanese army accused the Ethiopian military of executing seven captured Sudanese soldiers and a civilian following such clashes. Ethiopia’s ministry of defence ascribed the violence to militia forces and denounced the Sudanese claims as provocations. The episode highlights the risk of escalation due to competing claims and narratives.43

In July 2022, Abiy and Burhan met on the side-lines of an IGAD summit and agreed to form a joint committee to resolve the border dispute and re-open the strategic Metema–Gallabat border crossing – an important trade conduit between the two countries.44 However, renewed fighting in Tigray in September 2022 prompted Sudan to reinforce its positions along the border, heightening the potential for unintended escalation.45 Reciprocal visits by the two leaders – first by Burhan to Ethiopia in October 2022, then by Abiy to Sudan in January 2023 – have signalled an easing of tensions, but this has yet to be followed by noticeable changes on the ground.46

Even as the immediate prospects of an open conflagration have receded – with the Pretoria ceasefire largely holding in Ethiopia and communication between Ethiopia and Sudan on the one hand and Sudan and Eritrea on the other – the three militaries (Sudan, Ethiopia, and Eritrea) have remained deployed in large numbers close to one another, illustrating the overall dearth of trust. The regional implications of any escalation would be vast, including further civilian displacement and economic and food security consequences.47

Sudanese support for the TPLF and other Ethiopian opposition groups

Reports of Sudanese support for Tigrayan forces and other armed groups within Ethiopia have fed cross-border tensions. Diplomatic, Sudanese and Tigrayan military sources indicate that Sudan enabled the flow of supplies and materiel to both Tigrayan forces and rebels from the Benishangul-Gumuz region of Ethiopia, and allowed these forces to operate from eastern Sudan.48 The Sudanese authorities have denied providing materiel or training to Tigrayan forces.49

In addition, some 60,000–70,000 mainly Tigrayan refugees have fled to eastern Sudan since the start of the conflict.50 Some reportedly left refugee camps along the border to join TDF units operating from inside Sudan, seemingly with a focus on regaining all-important ground in western Tigray from Amhara security forces.51 Control of western Tigray – a key transit corridor and supply route from Sudan to Tigray – remains a strategic priority for the Tigrayans, and future arrangements for this territory’s administration are among the fundamental points of contention to be resolved in any durable solution to the Ethiopian conflict. 52

As of September 2022, tens of thousands of Tigrayan fighters were estimated to be present in eastern Sudan’s Gedaref state.53 This included a contingent of Tigrayan peacekeeping forces, formerly serving within the Ethiopian military as part of the UN Interim Security Force for Abyei (UNISFA), who had received political asylum in Sudan.54 Sudan also has sheltered Tigrayan political figures in Khartoum since early in the war,55 a reflection of the long-standing relationship between the Sudanese military and the TPLF.

Separately, Sudanese support to Gumuz rebels amid the Tigray conflict was said to include shelter of armed groups in Sudan’s Blue Nile state, bordering Ethiopia’s Benishangul-Gumuz region where the GERD is located.56 Gumuz rebels are reported to have used this area as a staging ground for attacks inside the Beninshangul-Gumuz region, in particular against convoys delivering construction materials to the GERD.57 As with Al Fashaga and its support to Tigrayan rebels, Sudan’s apparent tolerance of armed opposition activity within its borders is likely partly intended to place additional pressure on the Ethiopian federal government to reach agreement on the GERD.

Domestic posturing and the cross-border implications

With both Ethiopia and Sudan simultaneously undergoing transitions following the departure of long-standing authoritarian governments, the potential for domestic rivalries to drive or influence regional policy also raises the stakes in the relationship. As part of their political and strategic positioning, Sudan’s leading military figures, Burhan and Hemedti, have allied with opposing sides of the Ethiopian conflict. On the heels of reasserting Sudanese military control over Al Fashaga, Burhan and the SAF reinforced the long-standing Sudanese government relationship with the TPLF. Hemedti, by contrast, sought to cultivate a relationship with Abiy and federal government figures in Addis Ababa.58 However, recent efforts by Abiy and Burhan to restore relations will have undermined those efforts. Hemedti’s networking has included drawing closer to Ethiopia’s deputy prime minister and foreign minister, Demeke Mekonnen Hassen, as well as other Amhara leaders over shared business interests, including in agriculture and tourism.59 Hemedti has sought to balance engagement with Abiy and Amhara elites – the latter of which are focused on retaining control over western Tigray – with efforts to deepen his political appeal and influence on the opposite side of the border in eastern Sudan.60

While the ceasefire in northern Ethiopia has offered some promise of a lasting response to conflict, the primarily Ethiopian war has become a regionalized one. Sudanese, Egyptian and Eritrean actions can therefore ease or exacerbate the conflict – as has been most vividly demonstrated by Eritrea’s damaging involvement on the side of the federal government.

At present, there is impetus towards consolidating peace with Tigray. But these calculations could change, particularly if significant disagreements over implementation of the Pretoria Agreement should emerge.

The Ethiopian federal government’s ability and will to negotiate with the TPLF over core issues that led to war is conditioned by Abiy’s own domestic political calculations that rely on balancing Amhara, Afar, Oromo and other ethnonationalist interests, tensions within his ruling PP and the need to restart international assistance to help save a foundering economy. At present, there is impetus towards consolidating peace with Tigray. But these calculations could change, particularly if significant disagreements over implementation of the Pretoria Agreement should emerge. While Abiy consolidated his authority with an election win in 2021 and party reshuffles at the PP congress in March 2022, the positions of senior Amhara in the government remain important to the form and progress of mediations. Even if a sustained political settlement with Tigray is achievable, it could lead to further fracturing among Amhara or Afar constituencies and greater divisions between Ethiopia and its allies in Eritrea, if not carefully managed.61 Moreover, the varied international stakeholders involved – not least Egypt, Eritrea, the UAE and the US – have often worked at cross purposes, as they seek to resolve these crises in service of their own, sometimes incompatible interests.

Eritrean interests and interference

Eritrean president Isaias Afwerki’s deep animosity towards the Tigrayans stretches back decades, even before the 1998–2000 Eritrea–Ethiopia war, to the 1970s, when the Eritrean and Tigrayan leaderships alternated between cooperation over shared enemies and discord over divergent strategic visions. However, Afwerki’s unambiguous antipathy towards the TPLF in its current form means that Sudanese support to the Tigrayans pitted Sudan against the governments of two neighbouring countries. During the peaks of the Ethiopian conflict, this heightened the prospect of proxy or even direct interstate conflict between Sudan and Eritrea, feeding into a complex range of tribal dynamics playing out across their shared border.

Eritrean forces have been supporting the Ethiopian federal government in Tigray since the first month of the war.62 However, Eritrea has been at pains to avoid direct confrontation with Sudan’s military. This is despite the fact that, until recently, Eritrean forces were gathered extremely close to Sudanese territory, in western Tigray – including at Humera, a strategic border point between Sudan, Eritrea and Ethiopia. As of January 2023, some Eritrean units were reported to have moved out of major Tigrayan towns and back to the border area.63 However, reports of Eritrean forces’ presence in the region have continued. Afwerki was dismissive of calls for those troops to leave when asked by journalists following a visit to meet Kenyan president William Ruto in February 2023.64

Eritrean officials made several high-level visits to Khartoum in the last year, some of which included offers to mediate in the political crisis in Sudan.65 Eritrea maintains an influence in eastern Sudan, where tribes spanning the border area between the two countries are often in dispute. Historically, the Eritrean government has encouraged the settlement of the Beni Amer tribe in eastern Sudan, and sought to use its connections within that tribe to project its interests in Sudan. Eritrea offered to facilitate an August 2022 dialogue between eastern Sudanese tribes, an offer which was rejected by the Sudanese government.66

Prime Minister Abiy’s shifting stance on negotiations with Tigray, and the reported tensions this has caused with Afwerki, may have led to a change in approach by the latter. Afwerki is now deeply involved in Ethiopian politics; it is difficult to see how this will change. As part of the CoHA, the federal government has committed to ensuring sovereignty over its own territory and the removal of external forces from the region. Eritrean withdrawal will depend on whether Afwerki is reassured that the TPLF has been sufficiently weakened; in his eyes, this will likely require near full disarmament and demobilization of Tigrayan forces. However, that process is intended to take place simultaneously with the departure of Eritrean and Amhara forces from Tigray. If Eritrea does not fully withdraw, this could lead to a scenario where Ethiopian–Eritrean relations deteriorate once more and Ethiopian federal forces are pitted against their erstwhile allies.

With it being able to instrumentalize relationships with subnational groups such as the Amhara and the Afar,67 Eritrea’s commitment to removing the TPLF will continue to be a major obstacle and destabilizing factor in any attempts to reach a sustainable peace in northern Ethiopia.

Regional implications of Amhara discontent

The kinetic and political battle for control over western Tigray, a key fault line in the Tigray conflict and a focus of Sudanese interest across the border, is closely bound up in Amhara identity politics, as well as business interests which extend across the border into Al Fashaga. During the conflict in northern Ethiopia, Amhara, federal government and Eritrean interests converged over their shared antipathy towards the TPLF and TDF. The surge in Amhara nationalist sentiment was a significant motivational dynamic for the federal government’s prosecution of the conflict, and will continue to inform Abiy’s political stance as he seeks to resolve underlying tensions in the north.

Popular perceptions that the PP-led regional administration in Amhara serves the interests of the federal authorities over those of the Amhara people pitted Amhara nationalists against Abiy.68 This consternation was heightened by the federal government’s crackdown on the rapidly expanding Amhara Fano militia groups, which were at the centre of the fight against the TDF. The federal and regional forces arrested over 4,000 Amhara Fano, journalists and activists in May 2022.69 Moreover, in April 2023, the government’s decision to restructure the regional special forces under the command of the federal army and police sparked protests and armed skirmishes across the Amhara region. Amhara nationalists interpreted the decision as being targeted primarily towards curbing the Amhara region’s capacity for self-defence, and lessening its ability to maintain control of western Tigray and other contested areas.70

Despite the Amhara regional leadership overtly supporting the federal government’s decision, this dynamic contributes to heightened tensions between the two since the signing of the Pretoria Agreement. Such schisms and federal–regional strains are not new and, in part, reflect long-standing grievances from the TPLF-dominated era.

Amhara nationalism is also strongly connected to farming and agricultural interests along the fertile borderlands. Ethiopian farmers have grown sesame and other crops on both sides of the border for many years, with most of the cash crops produced in Al Fashaga exported via Ethiopia until the onset of conflict in Tigray and Sudan’s capture of Al Fashaga in late 2020. The Amhara capture of fertile land in western Tigray from Tigrayan control, meanwhile, has concentrated the dominance of the agricultural sector in the hands of influential Amhara political, business and security elites, some of whom are connected to the PP. Along with local investors, they are unhappy at the Sudanese takeover in Al Fashaga and the prospect of a shift in the agricultural export market away from Ethiopia.

Amhara territorial claims over Al Fashaga have to some extent been softened by the capture of western Tigray. However, this has not prevented the use of hostile rhetoric by senior national politicians seeking to demonstrate their regional credentials and protect their business interests. Mekonnen, the most senior Amhara in the federal government, has been vocal on this issue, claiming that Sudan invaded Ethiopian territory and that the land would be returned to Ethiopian control either peacefully or by force.70 This illustrates that subnational factors will continue to have important bearing on Ethiopia- Sudan relations.

De facto Amhara control over western Tigray and the prominence of their political and economic elites mean that Amhara sentiments and positions on Al Fashaga and the border will continue to influence and shape the federal government’s actions. Amhara discontent is intensifying as divides open between Amhara interests and federal actions, which are perceived in the Amhara regional capital, Bahir Dar, to be directed by Oromo elites. There are concerns that Abiy may see concessions over western Tigray as a way to consolidate a tenuous peace with the Tigrayans, including by exploring an interim administration for the territory ahead of a possible future referendum on the territory’s governance.71

- 21Holleis, J. (2023), ‘Ethiopia’s GERD dam: A potential boon for all, experts say’, Deutsche Welle, 8 April 2023, https://www.dw.com/en/ethiopias-gerd-dam-a-potential-boon-for-all-exper….

- 70Addis Standard (2023), ‘News Update: Heavy artillery fired in Kobo as protests engulf Amhara region following decision to dissolve regional special forces’, 10 April 2023, https://addisstandard.com/news-update-heavy-artillery-fired-in-kobo-as-….

04 Regional and international attempts to reduce cross-border tensions

A range of competing domestic, regional and international interventions reflect divergence over what stability for Ethiopia, Sudan and the Horn of Africa region entails and how to achieve it.

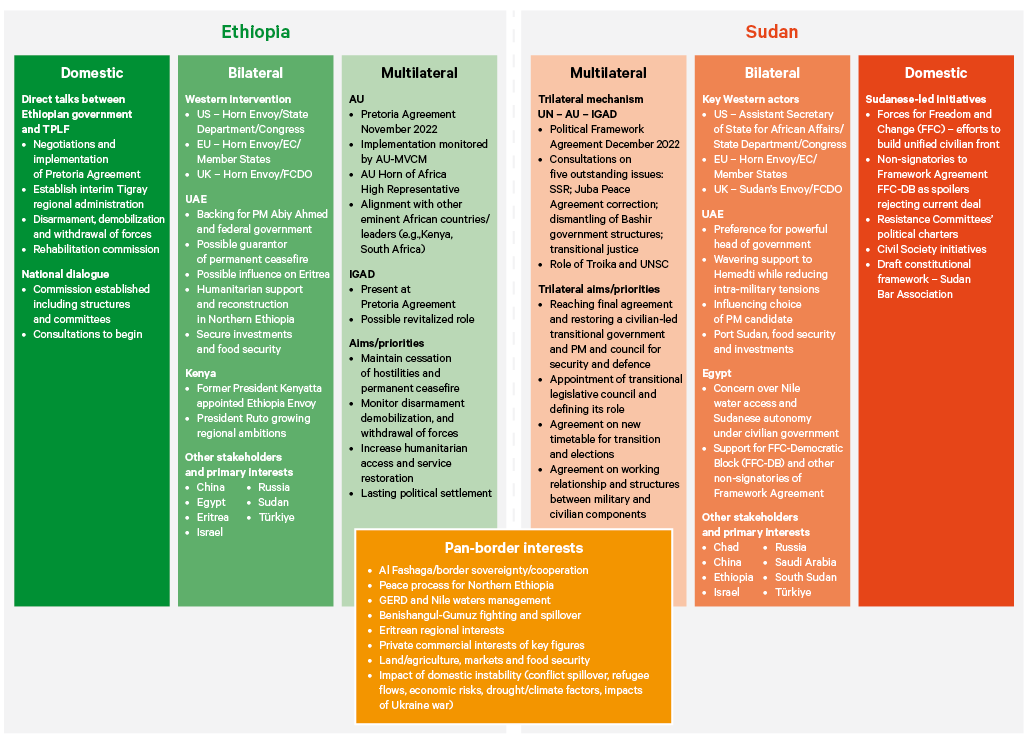

Recognition of the potential broad regional impact of a fragmenting Ethiopia or an unstable Sudan has driven considerable international attention and effort to ease the countries’ respective crises. In late 2022, the Ethiopian federal government and TPLF signed the AU-brokered – and Kenya-, South Africa- and US-backed – Pretoria Agreement, enabling talks to deliver a political settlement and sustainable solutions addressing underlying motives for conflict. In December 2022 – with considerable coaxing from the UN, the AU, IGAD, the US and others – Sudanese political and military stakeholders signed a Framework Agreement seeking to end that country’s political impasse. Both accords are fragile, though, with difficult existential questions involved for most stakeholders and fragmented political constituencies each demanding maximalist outcomes.

Figure 3. International and domestic responses to conflict and transition in Ethiopia and Sudan

Regional and international aspirations for broader regional stability would benefit from greater international focus on the array of factors linking Ethiopia and Sudan, and from meaningful coordination among international stakeholders, who have to date largely delinked the two crises.

Competing visions of regional stability

There is considerable disagreement among stakeholders in Ethiopia and Sudan, as well as regional and international parties engaged on the Horn of Africa, as to what stability for the region entails and how to achieve it. The clearest example of this is in the divergent definitions of stability held by Sudan’s FFC-CC, the broader pro-democracy movement that includes neighbourhood resistance committees, the two main military components and a splinter FFC component comprising former rebel movements and political parties, who have largely supported the coup.

These differing visions are often based on narrow interests or on the application of the specific foreign policy tools available to the governments and entities in question. For example, while some multilateral and bilateral stakeholders – such as the EU, Kenya and the US – support a negotiated solution in Tigray, others like Eritrea view a military solution that subdues the TPLF as central to their concept of regional stability. Other states – including China, Russia, Türkiye and the UAE – have been supportive of the federal government as the legitimate sovereign actor in Ethiopia. These states have provided or facilitated the supply to the government of military hardware to this end.

Weakening neighbours to impact the balance of power is hardly a novel strategy in the fractious Horn, but it requires restraint. While Egypt and Sudan see a weakened Ethiopia as more likely to make concessions over the GERD, they remain concerned over Ethiopia’s overall instability. Sudan is rightly anxious about the prospect of further cross-border spillovers of conflict and displacement, while Egyptian diplomats have rightly insisted that their country’s interests are not served by Ethiopia becoming too fragile.72

Limits to the effectiveness of the AU and IGAD

The AU has been party to the mediation processes to resolve the domestic crises in both Ethiopia and Sudan. Alongside IGAD, the AU’s continent-wide scope of works makes it the stakeholder best positioned to address cross-border tensions. Indeed, such work is fundamental to both bodies’ charters. The AU and IGAD have nonetheless struggled to fulfil this mandate and to operate effectively or decisively in such contexts. To protect its place in these processes, the AU has consistently invoked principles of subsidiarity (i.e. the prioritization of local actors to resolve conflict) to defend its diplomatic role, a doctrine backed overtly by UN secretary general António Guterres.73 This is despite an unconvincing record of intervention and a spate of coups across the continent in the past year, as well as concerns in some diplomatic circles over the AU’s impartiality.74

The AU has, in theory, an arsenal of available mechanisms to address issues in the Horn of Africa that feature a cross-border component. These include the AU High-Level Implementation Panel (AUHIP), AU Border Commission (AUBC), the Panel of the Wise, and the High Representative for the Horn of Africa (or ‘Horn envoy’). Unfortunately, these mechanisms have been either diluted (as is the case with the AUBC), unused (the Panel of the Wise), subject to serious internal AU political wrangling (Horn envoy) or simply moribund (AUHIP).75

Mandate limitations and oversteps, personality clashes and the personal political interests of key AU figures have all drastically limited the effectiveness of the interventions in both Ethiopia and Sudan.76 AU and US envoys have also been increasingly focused on addressing the more violent Ethiopian context ahead of Sudan’s political crisis. This is despite Sudan having played an important and underappreciated role in the Ethiopian conflict, and the fact that its own transition has slowed to a near halt.77

In Sudan, the AU, while in theory a helpful addition to resolving the country’s political stalemate, effectively diluted a UN process because of its own conflicted internal politics and an apparent reluctance to back a fully civilian-led transition in Sudan.78 In Ethiopia, the AU retained the overarching lead role in developing solutions to the conflict. While both the Ethiopian federal government and Tigray regional administration accepted AU-led mediation, the latter raised questions about the neutrality of the process, with Tigray regional president Debretsion Gebremichael criticizing the AU Horn envoy, former Nigerian president Olusegun Obasanjo, for his ‘proximity… to the Prime Minister of Ethiopia’.79 The Tigrayans were also concerned about the AU commission chairperson Moussa Faki Mahamat’s close relationship with the federal government.

For much of the conflict, the AU-led mediation worked at a slow pace. Staffing and financial limitations in Obasanjo’s team were reflected in the lack of urgency and results needed to avert a resurgence in violence.

For much of the conflict, the AU-led mediation worked at a slow pace. Staffing and financial limitations in Obasanjo’s team were reflected in the lack of urgency and results needed to avert a resurgence in violence.80 The international community sought to address questions around the effectiveness and impartiality of the mediation, pushing the AU to accept two co-mediators to support Obasanjo – former Kenyan president Uhuru Kenyatta (named as Kenyan envoy to Ethiopia), and South African politician Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka. Kenyatta’s participation provided an important counterweight to Obasanjo, proving instrumental to the TPLF’s acceptance of AU facilitation and to achieving a final agreement. The revised mediation structure ultimately helped to resolve long-standing credibility questions and brought the AU and Kenyan mediation tracks together. IGAD, which had struggled to secure a foothold in responding to the conflict – partly because its executive secretary is the former Ethiopian foreign minister, and partly because Sudan is the current chair of the organization – was also brought on board during the Pretoria talks.

On the GERD, Ethiopia has continued to back the AU to oversee talks, because it has felt able to influence the organization – not least because of its seat on the AU’s Peace and Security Council and because the bloc’s headquarters are located in Addis Ababa. However, Egypt and Sudan both favour the EU, the US and the UN to take this role. Western mediators had signalled their preference for a more comprehensive approach to the two countries’ shared issues that would consider the GERD, Al Fashaga, and questions of human rights violations in the Tigray conflict together. However, this approach was given short shrift by Ethiopia and contributed to the souring of relations between the federal government and Western capitals.81

In Sudan, the AU and IGAD have been leading negotiations to resolve the country’s post-coup political crisis as part of the ‘trilateral mechanism’ alongside the UN. This work resulted in the December 2022 Framework Agreement that enabled subsequent consultations among political and military actors on key thematic issues. In practice, the mechanism has afforded little meaningful progress to date. As in Ethiopia, the importance attached to the idea of African entities being seen to lead such a process obscured the real catalyst for progress: namely, the ‘quad’ grouping of countries comprising Saudi Arabia, the UAE, the UK and the US. Egypt, Israel and Russia, meanwhile, have all worked to ensure the continued primacy of security actors in Sudan, badly diluting any pressure applied by the US and other governments supportive of the pro-democracy movement.

The role of the UAE

The UAE has already illustrated its significant sway over events in Ethiopia and Sudan by helping the Ethiopian government to reverse its military fortunes in late 2021, and by providing early geopolitical and economic cover for the Sudanese military to remain in charge of that country’s transition.82 Following the October 2021 coup, though, the UAE has shown more nuanced understanding of the Sudanese context, striking a more constructive tone and seeking to defuse growing tensions between Burhan and Hemedti.83 With its financial strength, agricultural and strategic interests, and recent history of engagement in the Horn, the UAE has particular scope to enable or stunt progress towards sustainable solutions to the Ethiopian and Sudanese political crises. The Emiratis are well placed to become one of the guarantors of a lasting ceasefire in Tigray. They also mediated the most recent round of GERD talks, with several meetings taking place between March 2022 and January 2023, and could oversee a deal on the operation of the dam. Additionally, the UAE is able to leverage relations with the Sudanese military to influence the security forces’ actions domestically or regarding relations with Ethiopia.84

The UAE has equally shown that it can be a damaging influence in both contexts. In Sudan, it has ostensibly boosted both sides of Sudan’s military divide, though giving greater backing to Hemedti’s RSF.85 That support has undermined both Sudanese and international attempts to deliver a civilian-led transition to democracy and enabled the military’s October 2021 coup. In Ethiopia, meanwhile, the Emiratis have provided extensive military support to the federal government, including facilitating the transfer of drones that proved integral to the recovery of Ethiopia’s military in its brutal conflict with the TDF.86 Conversely, the UAE also sought to reinforce the ceasefire by providing aid to the Tigray region.87

Food security, economics and political motives for the UAE

Emirati interests in Ethiopia and Sudan – and in the stability and security of the two states – are based primarily on its desire to boost the UAE’s food security and on opening new markets for Emirati business. Because it has existing commercial relationships with all three countries that are set to expand in the coming years,88 it is likely that the UAE is keen to see a settlement on the use of Nile waters across the three countries affected by the GERD, in order to protect its agricultural investments: the UAE is dependent on food produced in the Nile river region and has invested heavily in farmland.89 In December 2022, a UAE consortium agreed a deal with the Sudanese government to invest $6 billion in developing the Red Sea port of Abu Amama and other economic assets, including 415,000 acres of farmland in Red Sea state.90 The deal was fronted by finance minister Gibril Ibrahim, together with Osama Daoud, chairman of the DAL Group and one of Sudan’s wealthiest businessmen. This deal remains controversial, partly due to having been agreed by the military-led government, and partly as Ibrahim, who is head of the Islamist Justice and Equality Movement (JEM), has so far refused to sign the Framework Agreement.

In Sudan, the UAE’s interests are also shaped by multiple factors, including continuing gold exports to Dubai and the Emiratis’ desire to control Red Sea access through the development of Port Sudan. Its involvement is also guided by its sense of Sudan being an Arab country within its sphere of influence, anxiety over the effects on domestic opinion of a successful civilian transition in Sudan and concerns over a resurgence of political Islam in East Africa and beyond.91 In Ethiopia, the UAE seeks stability – including suppression of non-state armed groups and denial of a new space for Islamist militancy – an investment destination, the consolidation of the Berbera joint port venture in Somaliland (despite uncertainty surrounding the status of the Ethiopian government’s 19 per cent stake), and the international gravitas bestowed by a successful diplomatic intervention.92 Its transactional approach to the region is a result of the UAE’s highly centralized and securitized decision-making on both Ethiopia and Sudan. Both files are run by security directorate figures, rather than civilian policy professionals.93 Additionally, the UAE’s national security adviser, Sheikh Tahnoun bin Zayed Al Nahyan, holds major commercial interests in a string of companies with interests in Sudan.94

The UAE’s involvement is guided by its sense of Sudan being an Arab country within its sphere of influence, anxiety over the effects on domestic opinion of a successful civilian transition in Sudan and concerns over a resurgence of political Islam in East Africa.

This approach serves neither the countries in the Horn nor the UAE well in the medium to long term. Supporting the Emiratis to take a less securitized approach which incorporates these factors may be the most effective way of improving outcomes in the region. This is not an unrealistic goal: in confidential communication with diplomats in 2021 the UAE expressed the belief that its policy on Sudan had delivered little to nothing in the way of positive outcomes and expressed a readiness to seek new approaches.95

Saudi Arabia’s interests in the Horn are shaped by similar factors to the UAE. However, its recent engagement on Sudan differs from that of its Gulf neighbour. Saudi concerns about worsening instability in Sudan under military rule informed their joint efforts with the US to bring the FFC-CC and military to the table for talks. The ‘quad’ held talks with officials in Khartoum in mid-February 2023, coinciding with a visit by six Western envoys.96 The UAE’s current stint on the UN Security Council may represent a further platform to incline the UAE to a less transactional approach to foreign policy.97

A narrow but influential vision

The UAE’s engagement on Al Fashaga exemplifies some of the opportunities and limitations in the Horn. While Eritrea, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Sudan and Türkiye all offered to mediate on the issue, only the Emirati effort gained traction with both the Ethiopian and Sudanese authorities. The UAE’s proposed deal to resolve the Al Fashaga tensions during talks in Abu Dhabi in April 2021 was ambitious, if also self-serving: the proposal specified a 99-year lease for the UAE on one-half of the territory. The idea was quickly rejected by both Ethiopia and Sudan for its indifference to local and national interests on both sides of the border. Despite this rejection, the proposal was resurrected in March 2022 as part of UAE-brokered talks over the GERD that showed crucial awareness of the links between the two issues.98 The UAE’s flexible and finance-oriented approach to both negotiations could still yield success. Vitally, the UAE has the financial capacity to assist the struggling economies of both Ethiopia and Sudan and could also possibly wield influence over Eritrean interests.

The US

With early progress on transitions in Ethiopia and Sudan stalled, Gulf allies increasingly assertive, and the war in Ukraine continuing (and consuming considerable diplomatic bandwidth), the US has, by and large, reduced its direct involvement in Horn affairs. The US’s sense of its scope to shape Sudan’s transition was tempered by the Sudanese military’s outright rejection of high-level, in-person US diplomatic demands not to undertake the forceful takeover of the transition in October 2021.99 In Ethiopia, meanwhile, relations between the US and the federal government were damaged by Washington’s open consternation at the brutal nature of Addis Ababa’s prosecution of the conflict in Tigray.

This reluctance to be involved contrasts markedly with the strong positive ambition of the US in the region prior to the Tigray war and the coup in Sudan, reinforcing the impression for some in the Horn of the US as a fair-weather interlocutor.100 The US government has been seen to be outsourcing elements of its Horn policy to regional allies such as Kenya, Saudi Arabia and the UAE, reducing the scope for US regional strategy to be effective and impactful.101 Shifting diplomatic focus to the conflict in Ukraine has further reduced US bandwidth to invest diplomatic capital in the Horn.102 Many Africa-focused observers and practitioners in Washington are seeking more thoughtful and robust US policies on the region, while some senior Africa policymakers seem to simply not believe in the US’s ability to effect change in an increasingly challenging and insecure region that has also seen a surge in geopolitical interest.103

The US relationship with Ethiopia’s federal government has deteriorated under the administration of President Joe Biden, which issued assertive calls for unfettered aid access, a ceasefire in Tigray and political talks, and the removal of Ethiopian access to the US duty-free trade programme AGOA in 2022.104 Biden’s policies met with the displeasure of Prime Minister Abiy, souring US–Ethiopian relations. This was partly why the US simultaneously sought progress and influence via regional partners with better relations, including Kenya and the UAE. The US has remained engaged on supporting direct and indirect mediation tracks, but the quick turnover of two US Horn special envoys since the departure of Jeffrey Feltman in April 2021 led some observers to question how committed the US is to this engagement.105 Feltman’s replacement, David Satterfield, himself ended a short stint in the role in the summer of 2022,106 and was succeeded by Mike Hammer, who has received direction from State Department principals that his chief focus is to be Ethiopia, although in actual terms his remit is limited to Tigray and does not include other conflict areas in the country.107

Special Envoy Hammer did play an integral role in both bringing the Ethiopian federal government and the TPLF to the table and finding the concessions needed to secure the November 2022 ceasefire. The government’s motivation for signing the Pretoria Agreement was partly a response to the worsening economic situation in the country, and the hope that the deal would lead to improved relations with the US and other Western partners, including the restart of suspended development assistance and trade programmes, as well as support for reconstruction efforts in the north. Abiy’s invitation to the US–Africa summit in December 2022, followed by Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s visit to Addis Ababa in March 2023, signals a gradual normalization of relations between the US and Ethiopia, subject to progress towards sustained peace in Tigray and the northern part of the country.

Likewise, the US was vital to getting Sudan’s problematic Framework Agreement signed, though the deal’s severe limitations given the ongoing primacy of the military in Sudanese politics has made its value and relevance a hotly debated topic in Khartoum and beyond. A key US motivation for pushing the deal through was to return to office an acceptably pro-democracy civilian transitional government that would enable the reopening of funding flows to Sudan.108 The starkly divided Sudanese military has to date been broadly unwilling and unable to endorse such a step, though hopes have been boosted by the breakthrough of reaching an agreement to form a new civilian-led government by mid-April 2023.

In a 15 October 2021 email to then-envoy Jeffrey Feltman and State Department staff, Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs Molly Phee acknowledged that there had been some ‘confusion and discontent about who is doing what’ in Ethiopia and Sudan.109 US officials themselves expressed worry that, by separating responsibilities – with Hammer focusing on Ethiopia and Phee (and, more recently, the new US ambassador in Khartoum, John Godfrey) overseeing engagement in Sudan – the US is limiting its ability to understand the links between the two contexts, and to strategize and act accordingly.110

Other geopolitical stakeholders have taken advantage of the US’s tentative approach, and the limits to its bandwidth, to promote their own interests more forcefully. For example, Israel and Russia have expanded their influence in Sudan through closer military ties.111 Russian interests in Sudan are largely overseen by President Vladimir Putin’s apparent confidant Yevgeny Prigozhin.112 Prigozhin’s role includes oversight of the paramilitary Wagner group, whose expanding activities in Sudan include gold- and uranium-mining and the export of military hardware, as well as training and strategic communications for Hemedti’s RSF.113 Russia has also lobbied the Sudanese authorities to allow it to establish a naval base at Port Sudan on the Red Sea. Russia’s expansion of economic and political interests in Sudan and several neighbouring countries are viewed by the US and analysts as a key component of feeding into renewed ‘great power’ competition.114 US caution on the Horn, along with the ebbing and flowing of backing by Saudi Arabia and the UAE, has enabled Hemedti and the RSF, as well as Burhan and the SAF, to act with little restraint, although the US Congress has discussed the prospect of imposing sanctions on the former.115

05 Policy implications for international stakeholders

Cross-border tensions and interlinked crises in Ethiopia and Sudan jeopardize security and development across the Horn of Africa. International partners should coordinate on responses that address the intersection of those crises and causes of instability both within and between the two countries.

Both Ethiopia and Sudan will take many years to recover from their internal political and economic crises. Conditions in each country could worsen before they improve. The fragile ceasefire in the Tigray region and rising unrest in other parts of the country show how far Ethiopia remains from a sustainable reduction of violence. Even if the current peace deal holds, large parts of northern Ethiopia will struggle to recover from the damage caused to the country’s social fabric by interethnic fighting. Across the border in Sudan, meanwhile, the scramble for control of the political transition among a divided military, a splintered civilian cadre and a revived Islamist old guard indicates an uncertain future. In both contexts, interested regional and geopolitical forces further complicate attempts to deliver sustainable, inclusive, civilian-led governance that works for the countries’ large and diverse populations.

These crises, if unaddressed, have the potential to become much more dangerous than they already are. Stabilizing the intertwined transitions in Ethiopia and Sudan will require considerable and sustained international diplomatic, financial and technical assistance.