V Sloyan, Aug 25, 2022

Wellcome Collection holds 27 Ethiopian manuscripts, which we are converting into XML using the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) standard. We are also taking the opportunity to research the custodial history of the manuscripts, specifically how, when and from whom Wellcome acquired them.

Overview of the manuscripts

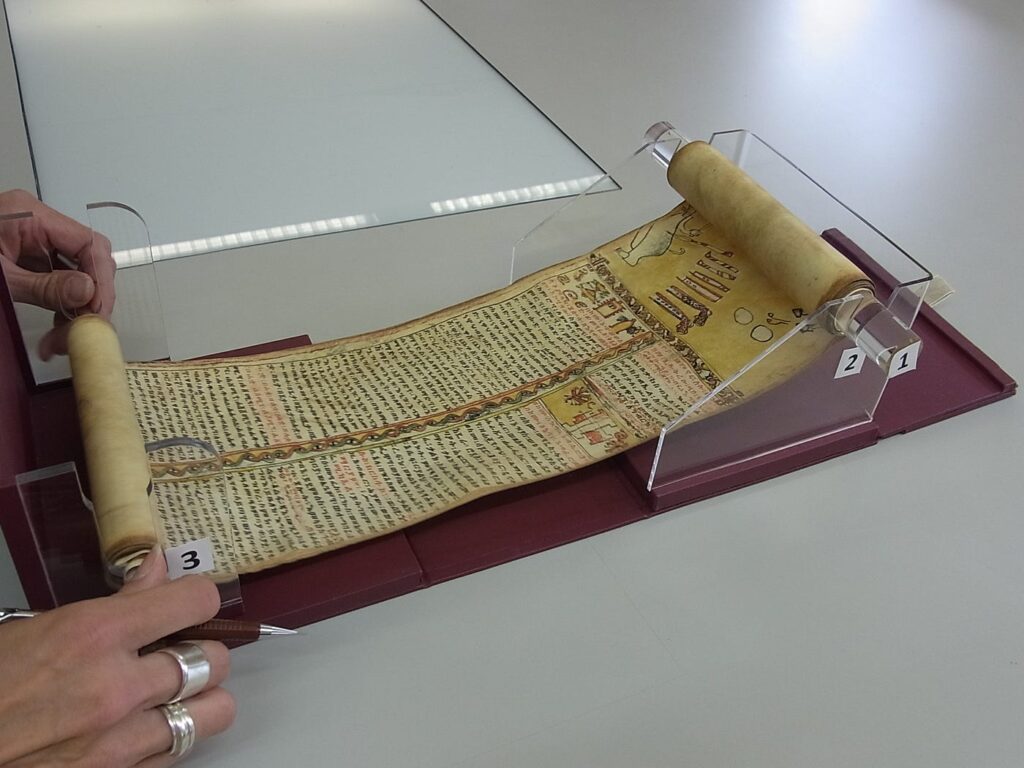

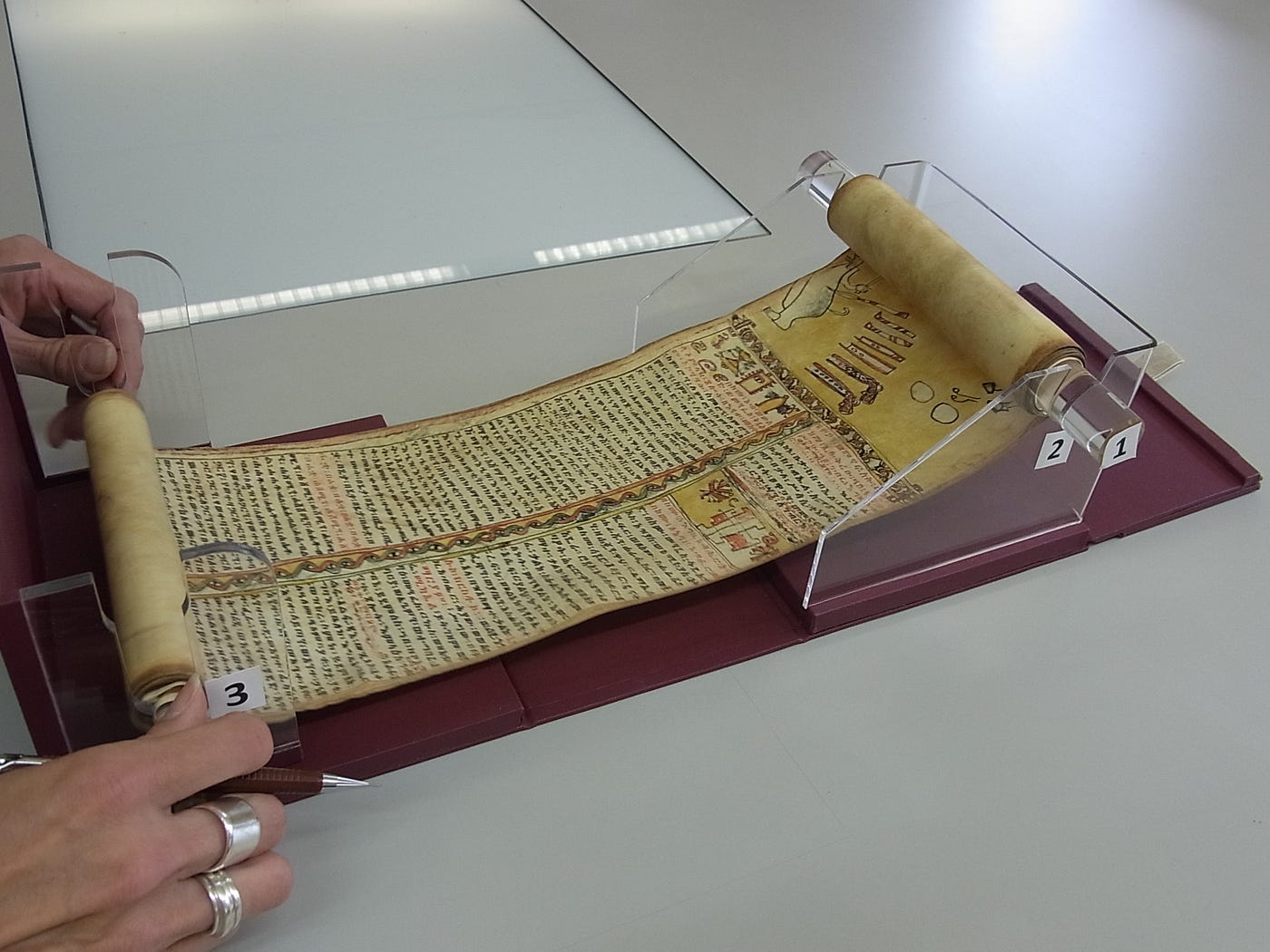

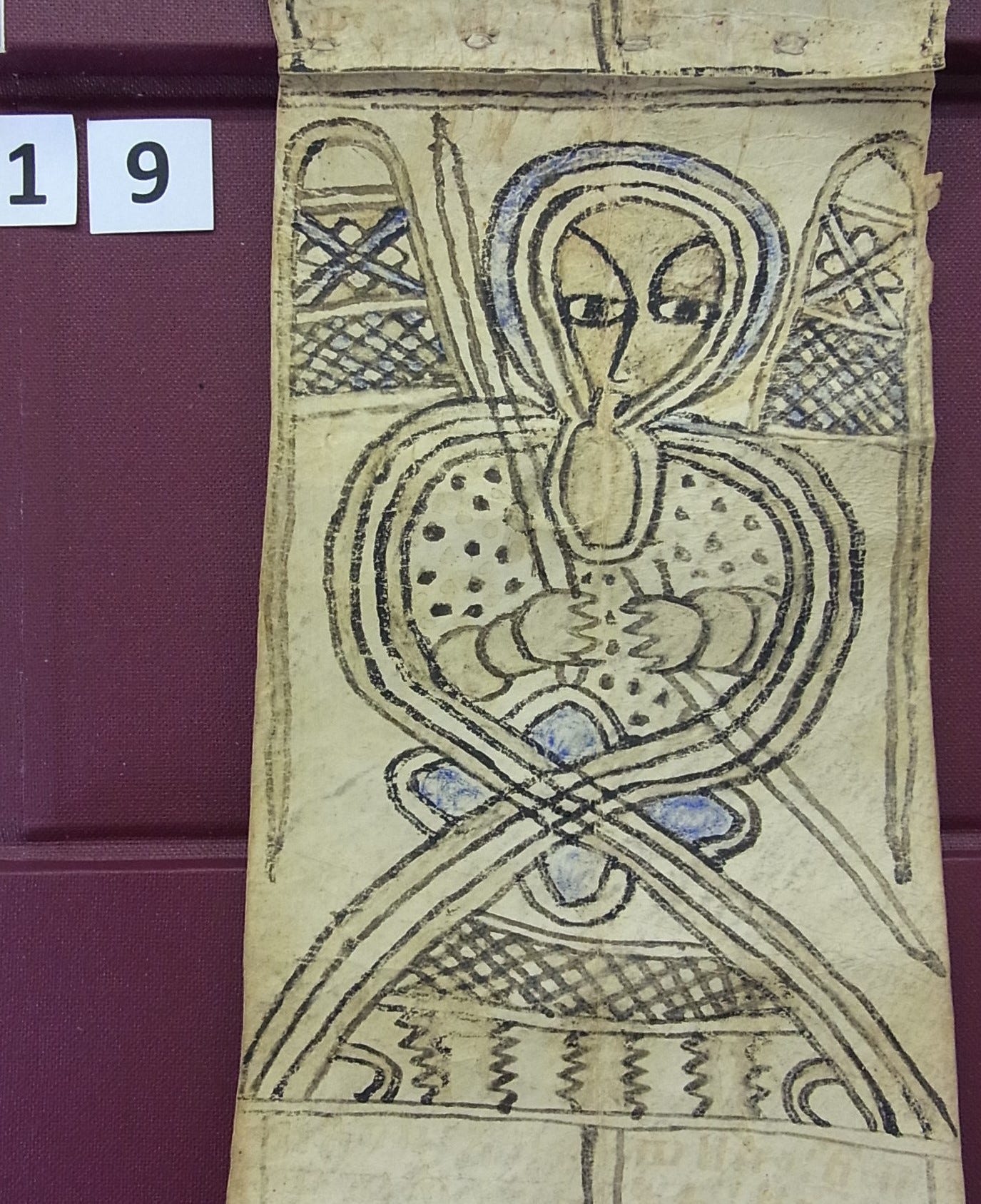

The first catalogue of Ethiopian manuscripts was produced in 1972 by Stefan Strelcyn, Reader in Semitic Studies at Manchester University, and covers the 16 vellum scrolls and bound volume Wellcome held at that time. The scrolls contain a mix of magic spells and Christian prayers designed to fight demons and the diseases they bring and to keep people in good health. They would have been composed for a particular individual and made of pieces of vellum stitched together to be equal in length to the height of the sick person. Strelcyn labelled this blend of religion, magic and medicine as “magico-medical scrolls”. The volume contains a treatise on divination and some magico-medical content.

In 2005, whilst studying the manuscripts catalogued by Strelcyn, the researcher Resoum Kidane offered to catalogue an additional 8 manuscripts that had been acquired since 1972. The resulting catalogue addendum was used internally by Wellcome staff but never published.

Finally, in around 2015 Katya Gusarova, an Ethiopian specialist from St Petersburg, undertook a placement at Wellcome and created a new catalogue for all 25 manuscripts, plus two more acquired since 2005. This metadata was added to our cataloguing system and made available via the online catalogue.

The ten manuscripts acquired since 1972 comprise six more magico-medical scrolls and four bound manuscripts containing Christian texts.

Not much is recorded in any of the catalogues about the provenance of the manuscripts. However, the 1972 Strelcyn catalogue provides accession numbers and gives basic details for some, including the statement “Taken at Magdala in 1868”, suggested a connection between some of the manuscripts and the 1868 British Expedition to Abyssinia.

British Expedition to Abyssinia

Tewodros II, Emperor of Ethiopia since 1855, established a fortress at Maqdala along with a church intended to become an important centre of study and worship. To this end, he accumulated manuscripts and other texts, many of which were taken, possibly forcibly, from other Ethiopian churches.

Tewodros II was an unpredictable ruler with an unstable reign and in the 1860s he took hostage the British Consul Charles Cameron, along with various other British and Ethiopian citizens. They were imprisoned and then taken to the fortress of Maqdala.

In response, on 21 August 1867 Britain announced the launch of a military rescue mission and punitive expedition to Ethiopia undertaken by the Bombay Army led by Sir Robert Napier. During the journey to Maqdala the British negotiated with locals and the Emperor’s opponents and gained support of the two most powerful northern princes. This allowed the British to spin the expedition as a rescue mission based on the conquest of a single fortress being ruled by an unpopular, despotic emperor, rather than a foreign invasion. In this, the expedition was typical of the continual warfare waged by the British across much of the world throughout the late Victorian period.

The British arrived on 9 April and the Battle of Maqdala began the next day on a plateau. This was followed by a short siege of the fortress. The British entered the fortress on 13th April to find that Tewodros had shot himself rather than be captured. At this point his army surrendered.

Before destroying the fortress, the British entered the treasury and looted the large collection of manuscripts, books and objects found there. Officially the loot was gathered by the British army “prize master” and organised by the army’s Prize Committee, but it is almost certain that smaller and less valuable items were kept by individuals and smuggled out.

The officially looted objects required 15 elephants and 200 mules to move them to Delanta where a 2-day auction took place. Over 300 books and around 350 manuscripts were purchased by the British Museum via its representative, Mr Holmes, present as the expedition’s archaeologist.

Tracing the fate of the other manuscripts taken from Maqdala has proved tricky, in part because they were seen as less valuable and easier to be kept by individual members of the expedition. However, it is estimated that a couple of hundred were likely smuggled out of Ethiopia and sold in European auctions.

Thus, we know many manuscripts and other documents left Ethiopia after the expedition and ended up in Europe, but can we say with any certainty that any of them were acquired by Wellcome?

Origins of the Wellcome manuscripts

Firstly, the later two catalogues do not include any provenance or acquisition information and examining the physical items has yielded little information. We know that three were purchased from reputable booksellers in 1991 and 2000. Further investigations into the other seven are ongoing.

More promisingly, we have accession numbers for the 17 manuscripts catalogued by Strelcyn, though one appears to be incorrect. Looking these up in Wellcome’s accession registers, we learnt they were all purchased at UK auctions between 1915 and 1934. Luckily, Wellcome has retained most of the sales catalogues from auctions attended in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and so we looked at the lot entries to see if they recorded any provenance information.

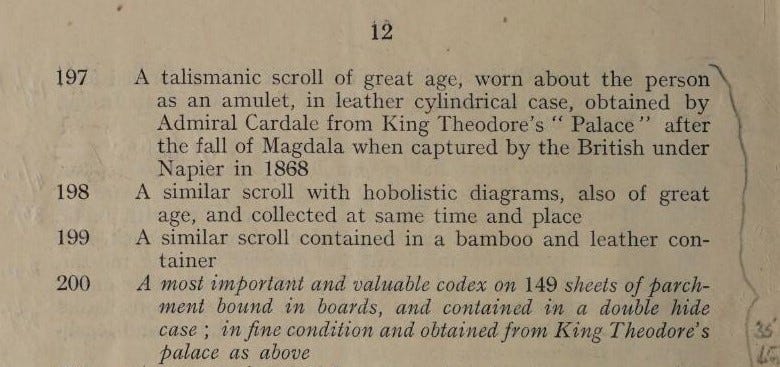

Three sales catalogues could not be located, and several others either had no provenance information or so little to be as good as useless (e.g. “the property of a gentleman”). That still left five. Three entries included the statement “formerly formed part of King Theodore’s Library at Magdala” (Theodore being the anglicised name of Tewodros) and two went even further: “obtained by Admiral Cardale from King Theodore’s “Palace” after the fall of Magdala when captured by the British under Napier in 1868″.

Admiral Charles Searle Cardale (1841–1904) was a lieutenant and second in command of the Naval Rocket Brigade in the Abyssinian Expedition, seeing action in the Battle of Maqdala and the siege. He was twice mentioned in despatches and promoted to Commander for these services, being awarded the Abyssinian Medal. He reached the rank of Vice-Admiral in 1899 before being placed on retired list on 3 March 1900. He was awarded the rank of Admiral on 15 March 1904 shortly before he died.

Thus, it seems reasonable to state that five of Wellcome’s manuscripts were purchased in the UK after being taken from Maqdala by the British Armed Forces as spoils of war. The origins of the remaining 12 manuscripts catalogued by Strelcyn is unclear. They could have been taken during the 1868 expedition, but equally they could have legitimately left Ethiopia and later been bought by Wellcome. We do not have enough information to say either way with any confidence.

Wellcome is now asking itself what, if anything, should be done about the five manuscripts known to have come from Maqdala. This is a contentious subject and there are longstanding campaigns to repatriate such material. Should Wellcome embrace this and return the manuscripts? If this were to occur, it would not be the first time Wellcome has repatriated Ethiopian material.

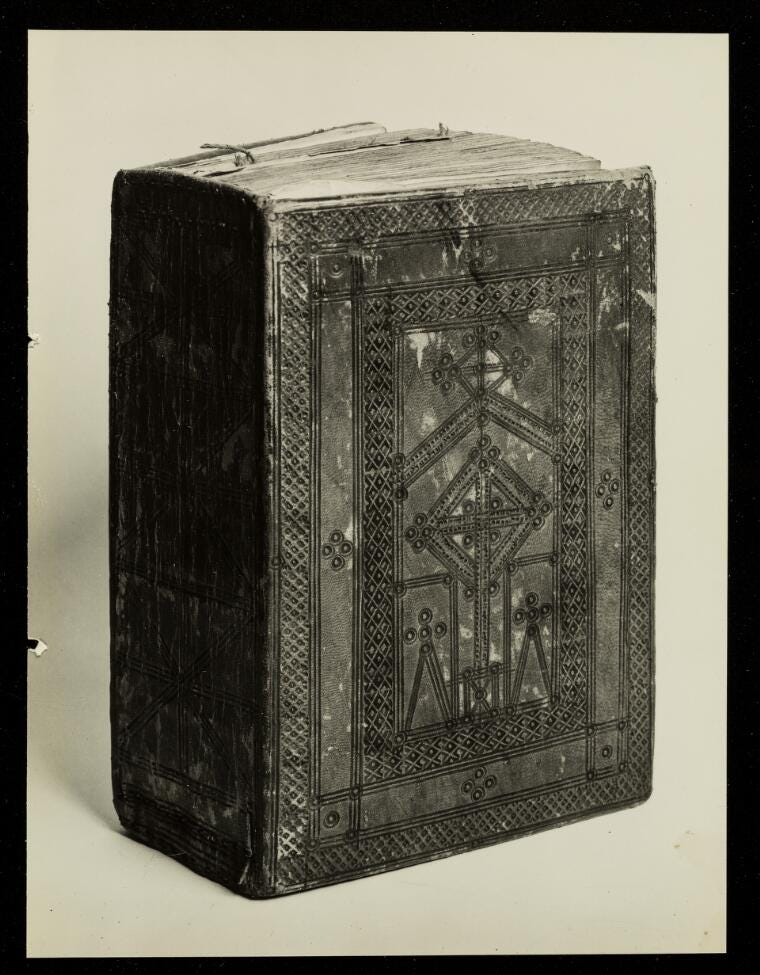

In May 1930 Wellcome purchased “King Theodore’s Bible” from a Sotheby’s auction. It had been taken at Maqdala by a Major Leveson and held in private keeping until 1930. After Henry Wellcome’s death the trustees of the newly formed Wellcome Trust sold various library and museum items that were deemed to be not in scope. The bible was identified, but according to papers in the archive the Trustees felt uncomfortable selling it on the open market given its origins. Instead they contacted the Foreign Office to see how the government felt about offering it to the Ethiopian Emperor, Haile Selassie. This was approved and the bible was presented to the Emperor in 1942 by government officials.

Thus, repatriation is not an impossibility. In the meantime, and as a first step, the new TEI catalogue records being generated will include the custodial history, where it can be ascertained. These records will improve the discoverability of the manuscripts and aid in Wellcome’s intention to be open and transparent about our collections. We are also exploring the possibility of digitising the manuscripts, to enhance their accessibility to researchers all over the world. Though the fragility of the scrolls means this needs to be investigated and planned carefully